Margo Rejmer – by Katarzyna Lasoń – Sent to VTRS by author, CC BY-SA 4.0

A book on the past and present of Bucharest, where the destinies and painful experiences of a society that has not yet managed to come to terms with the communist past intertwine. An interview

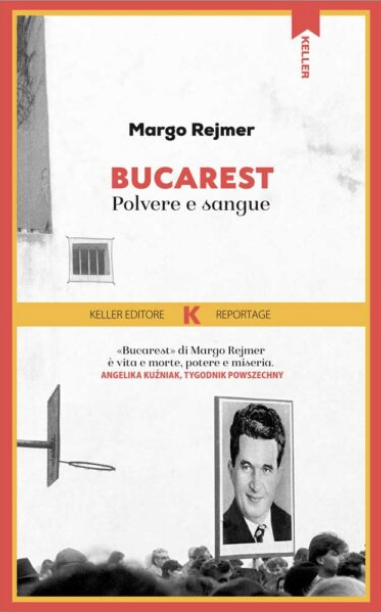

“Bucharest, dust and blood” by the Polish writer Margo Rejmer – edited by Keller Publisher – is a journey into the capital of contradictions, where one constantly wanders through urban chaos, the anarchy of moving cars and the uncontrollable energy of its inhabitants. The chronicles that make up this long report offer the reader a city in continuous transition, passing through physical places, political ideology and crossed destinies. Rejmer’s fluid narration allows us to understand the historical circumstances, the consequences of the absurd dictates of Ceaușescu’s regime, the traumas inflicted on the population and the slow tearing of the social fabric.

What does Bucharest represent in the eyes of a Polish writer?

I have the impression that people who live in Warsaw, a city that was wiped out during WWII, idealize the image of the lost city, the city that was taken from them. This new, reconstructed Warsaw is an unattractive girl, tidy, in a clean apron, who tries very hard: she polishes the few resources she has, she thinks pragmatically just to have a decent life without great aspirations. Bucharest is in some ways the opposite of Warsaw: it is old but at the same time beautiful, bitter but still full of imagination. Warsaw sometimes seems boring and rational to me, Bucharest is flamboyant and unpredictable. An architectural vivacity and courage, an excess of styles: Byzantium and oriental Gaudì, totalitarian postmodernism and the Orient. At first glance, nothing fits in it, and the beauty is hidden behind the walls. Compared to the Polish one, Romanian communist architecture is scaled down, disproportionate, overwhelming in its aspirations, even brutal. But to understand Bucharest, one has to see all the layers of her. In “Bucharest” the complicated history of Romania is reflected in the city’s extraordinary architectural diversity.

The book is full of chronicles of life under the Ceaușescu era, she gave voice to experiences that had no voice. Was it difficult to gain the trust of your interlocutors and collect their memories?

Research in Romania was much easier than my subsequent job in Albania. Although Romanians have a traumatic history and the phrase “please don’t mention my name” was the refrain of many conversations, I got the impression that they welcomed me. As if they are ready to tell their stories and are just waiting for someone to listen to them. I easily found interesting characters and created new circles of friends. When I arrived in Romania, I seemed to understand reality intuitively. In the case of Albania, the first year I went around in circles, bouncing off walls. Nobody wanted to talk to me about the past. I had to learn to think like Albanians to understand the extent of their distrust of society.

Breaking the bond between citizens by instigating doubts and fears was a recurring practice during communism in Eastern European countries. What consequences have these scars left on the evolution of Romanian society today?

Romania has never come to terms with its past. Since 1989, the institutions have been controlled by groups heir to the Communists or associated with the previous system, so there is no pressure from the elites to come to terms with the past. The Securitate, the secret police, had great influence over people’s lives, yet was never held accountable for its activities. The lack of historical knowledge and institutional discussions about the past favor the mythologizing of communism and the deep disillusionment with politicians leads to the unexpected popularity of the myth of Nicolae Ceaușescu. Today, more than 60 percent of Romanians believe that Ceaușescu was the best president in Romania’s history. “He may have made mistakes, but at least he gave work and dignity to people. And now? Even though we are part of the European Union, five million people have left the country: is this the best life?”. 52 percent of Romanians agree with the statement that Romania needs a strongman who doesn’t look to the parliament when governing the country.

In the book there is a passage where it is said that “freedom is like air: when you have it you don’t feel you need it, but when you lack it you start to suffocate”. What does freedom mean for the new generations of Romanians?

Freedom today has pragmatic aspects, it is associated with a sense of self-fulfilment, with the right to decide for oneself and with the influence of civil society on political life. To what extent is an ordinary person able to stop or limit the pathologies of power by taking to the streets? Since 2013, huge street protests, with hundreds of thousands of people, have swept through Romania, against corruption, the degeneration of politicians and against those who plunder the country. Civil society managed to save the Rosia Montana region from exploitation and destruction, and after the fire at the Colectiv club, mass protests sparked a great discussion about corruption and pathologies in the health service. But now public opinion is deeply tired. The new politicians who entered the government on the wave of social protests have not proved to be as effective as expected, and there have also been allegations of corruption around them. Romanians trust neither the president, nor the parliament, nor the government. For many, freedom means the right to leave their country to find a better place to live.

What are your next projects for Italian readers? Any new releases coming soon?

Keller Editore is about to publish my non-fiction book on communist Albania, “Mud sweeter than honey”. At the moment I am working on a collection of short stories on the Balkans and, once finished, I will return to write another reportage on contemporary Albania, “Ditë të bukura na presin” (Beautiful days waiting for us, nd)

Have you thought about a subscription to OBC Transeuropa? You will support our work and receive preview articles and more content. Subscribe to OBCT!