The author is the chairman of the American Council on Foreign Relations

One advantage historians have over journalists has to do with time. Not so much in the sense that they don’t have closures, but that they have a deeper perspective afforded by the years—or even longer periods—between events and writing about them. Twenty years, of course, is not a long time in historical terms, but when it comes to understanding the war that the United States launched against Iraq in March 2003, that is all we have for now.

No wonder that even two decades after the start of the war, there is no consensus on its legacy. This is understandable because all wars are fought three times. First comes the political and domestic struggle over the decision to go to war. Then comes the real war with everything happening on the battlefield. And finally there is a long debate about the meaning of the war: weighing the costs and benefits, determining the lessons learned and formulating forward-looking policy recommendations for the future.

The decision to intervene

The events and other factors that led to the US decision to go to war against Iraq remain unclear and the subject of considerable controversy. Wars basically fall into two categories: one is necessary, the other is voluntary. Unnecessary wars occur when vital interests are at stake and there are no other viable options to defend them. Wars of choice are interventions initiated when interests are not vital, when there are options other than military force that could be used to protect or advance those interests, or when both options are valid. The Russian invasion of Ukraine was a voluntary war, Ukrainian armed defense of its territory is inevitable.

The war in Iraq was also a classic voluntary war: the US did not have to fight in it. However, not everyone agrees with this assessment. Some argue that there were indeed vital interests at stake because Iraq was believed to possess weapons of mass destruction that it could use or share with terrorists. Proponents of the war had little or no confidence that the US had other reliable options for eliminating Iraq’s alleged weapons of mass destruction.

Moreover, after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the decision reflected a determined unwillingness to tolerate any risk to the US. The idea that al-Qaeda or any other terrorist group could attack the US with a nuclear, chemical or biological weapon was simply unacceptable. The main representative of this opinion was then Vice President Dick Cheney.

Others, including President George W. Bush and many of his top advisers, were apparently motivated by additional considerations, such as pursuing what they saw as a major new foreign policy opportunity. After 9/11, there was a widespread desire to send a signal that the US was not only on the defensive, but also active in the world as a proactive force that could take the initiative and achieve great effect.

Whatever progress has been made in Afghanistan since the US invaded and removed the Taliban government that provided a safe haven for the al-Qaeda terrorists who planned and carried out the 9/11 attacks has not been enough. Many in the Bush administration were motivated by a desire to bring democracy to the entire Middle East, and Iraq was seen as the ideal country to set this process in motion. The democratization of this country should have been an example that others in the region could not resist. And Bush himself wanted to do something big and bold.

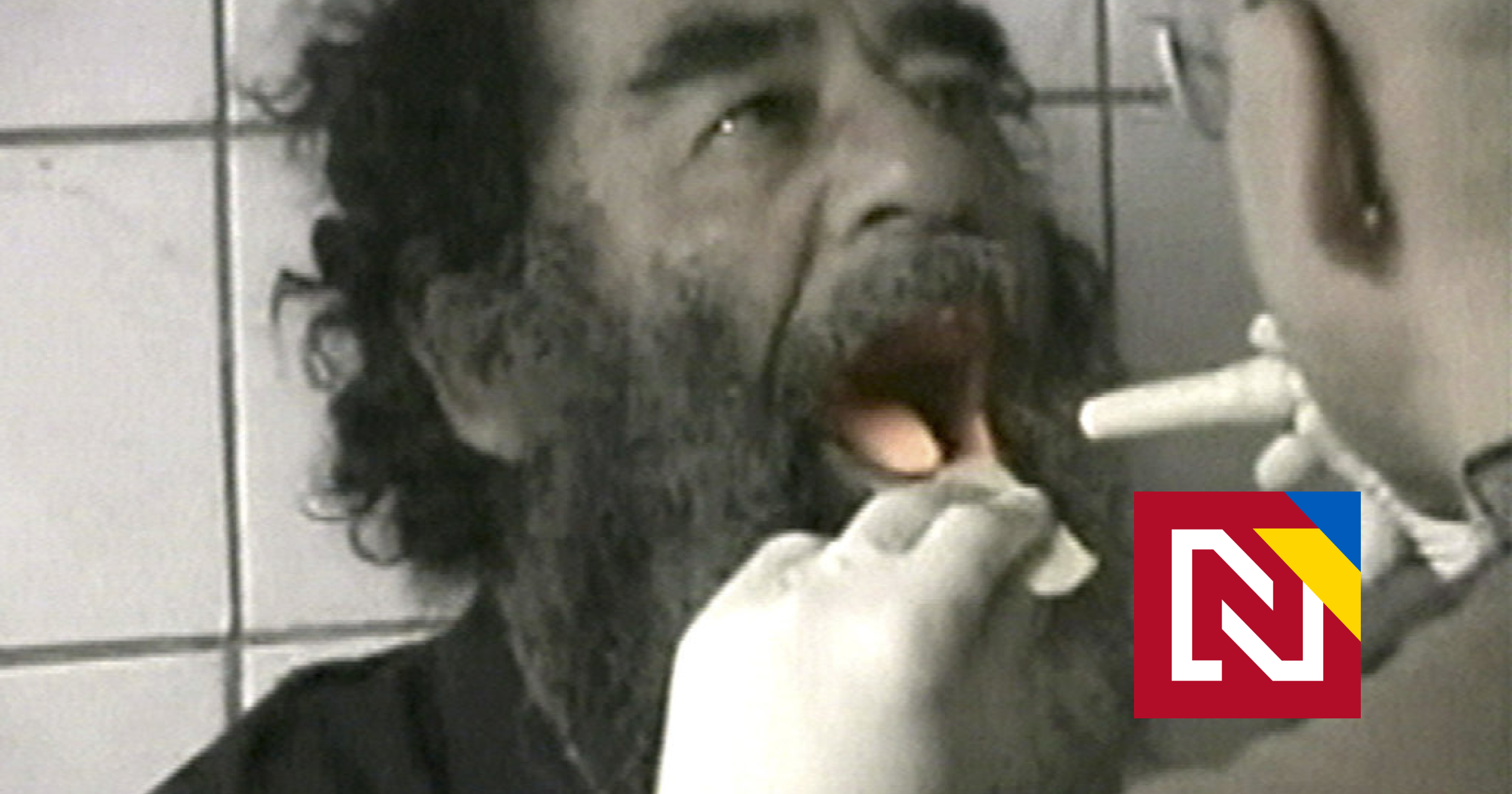

At this point, I should clarify that I was part of the presidential administration at the time as head of the Department of State Policy Planning. Like virtually all of my colleagues, I thought that Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction (WMD), namely chemical and biological weapons. Nevertheless, I was not inclined to the idea of going to war. I believed that there were other acceptable options, notably measures that could slow or stop the flow of Iraqi oil to Jordan and Turkey, as well as the possibility of cutting the Iraqi oil pipeline to Syria. If this were to happen, it would put considerable pressure on Saddam to allow inspectors access to locations where the weapons were believed to be located. I thought that if he did refuse these inspections, the US would be able to launch limited attacks on these facilities.

I wasn’t particularly worried about Saddam flirting with terrorism.