Two coupled steel tubes, a pair of hoses, a transducer: the innovation from a laboratory at the University of Mexico is inconspicuous, smaller than a ruler – and yet it is supposed to achieve great things. “We want to use this to remove microplastics from river and sea water in the future,” says Menake Piyasena. The researcher is actually not a plastics expert. “Until now, we have used sound waves to focus biological cells and then study bioprocesses. Then we had the idea: What if we apply this technology to microplastics?”

Piyasena’s team implemented the idea and used a transducer – similar to that used in a doctor’s office – to generate standing sound waves in the tubes, which now exert forces on plastic particles instead of on biomolecules. “We can use this to direct plastic particles in the water in certain directions. This works in a similar way to magnetic parts being attracted by a magnet,” explains the researcher.

The team recently presented a first prototype at the spring conference of the “American Chemical Society”. The researchers reported that it works just as well with pure water as with roughly cleaned river water from the Rio Grande. According to their own statements, they were able to pull out between 70 and a good 80 percent of the microplastic particles that they added for their experiments via sonication.

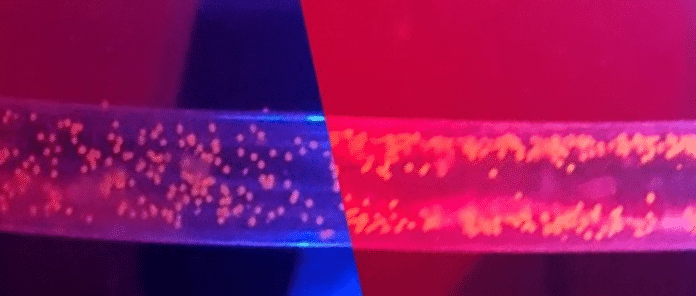

Microplastics are naturally scattered in flowing water (left), but turning on the sound waves concentrates the particles on the sides of the pipe (right), making them easier to remove.

(Picture: Menake Piyasena)

Tens of tons of microplastics worldwide

The pressure to act is great. After all, tens of millions of tons of plastic from old bottles, fishing nets, flip-flops and countless other products are floating in waters around the world, which eventually break down into tiny particles. If these are smaller than five millimeters, they are called microplastics. Microplastics are also introduced from tire abrasion, from artificial turf, fleece jackets and other synthetic textiles as well as from the plastics industry.

The tiny plastic, which can also contain questionable additives, are distributed all over the world. They have also been found in the Antarctic and on the peaks of the Alps, in animals and humans. It is still largely unclear what consequences this will have for ecosystems and health.

Compared to filters and sieves that are commonly used to remove microplastics from water – from laundry bags for the washing machine to membrane filters for drinking water treatment – according to Piyasena, the ultrasonic method has one advantage above all. “The tubes do not clog over time and do not require extensive maintenance,” says the researcher.

With gel against microplastics

It is not the first attempt to remove microplastics from water with filterless systems. The non-profit greentech company Wasser 3.0, for example, relies on a hybrid silica gel that consists primarily of quartz sand and acts like a chemical glue on the particles. A few milliliters in around 2,000 liters of wastewater from a sewage treatment plant or seawater are enough for the gel to crosslink the plastic particles into larger, popcorn-like lumps that then collect on the water’s surface. From there they can, for example, be fished off with a sieve or automatically pushed into a collection container with a skimmer.

The award-winning company wants to be able to remove around 95 percent of the microplastic particles with this method. In addition, any large quantities can be treated by simply connecting the stirred tanks in series. The process has already completed an initial long-term test in the Landau sewage treatment plant.

With cyclone filter and electric current

Researchers at the Fraunhofer Institute ILT in Aachen, on the other hand, want to defuse the microplastic problem with a so-called cyclone filter: a cylindrical film with holes ten micrometers in size. A rotor moves around this filter, which creates suction through the negative pressure so that no particles get stuck. And scientists from South Korea and Canada rely on electrochemistry, on electrodes that use electrical energy to oxidize microplastics in the water to form carbon dioxide and water.

The idea of using ultrasound to collect microplastics is also not new, admits Piyasena’s colleague Nelum Perera. “But so far, research groups have only worked with very small amounts of water and with microplastic particles that were smaller than 100 micrometers, i.e. smaller than the diameter of a hair,” says the researcher.

The team from Mexico, on the other hand, not only successfully tested the acoustic microplastic remover with particle sizes of up to 300 micrometers, but also with various common plastics.

Recommended Editorial Content

With your consent, an external YouTube video (Google Ireland Limited) will be loaded here.

Always load YouTube video

Aufnahme vom: American Chemical Society Meeting Newsroom

Microplastics are not just microplastics

During their tests, the researchers also made a discovery: the particle distribution depended on the water quality. In pure water, all the particles collected in the middle of the water flow, so the purified water could be drained through hoses at the edges.

However, if there were surfactants in the water, such as those found in detergents or fabric softeners, the smaller particles behaved differently than the larger ones up to around 180 microns. The tiny ones continued to float in the middle, while the larger particles were pulled outwards. In order to tap both fractions, the researchers finally connected two steel tubes in series.

“We were able to remove around 70 percent of the smaller and 82 percent of the large plastic particles,” says Perera. The team achieved similar results with river water and with water from the campus pond. For their tests, the researchers cleaned the water of coarse dirt and added a defined amount of microplastic particles of different sizes.

Tests with seawater are pending

However, water purification with ultrasound takes time. It currently takes about an hour and a half to purify a liter of water, says Perera. The next goal of the Mexican team is therefore to bundle the tubes into larger devices and to start the first tests with seawater soon.

Whether and when the method can be used for practical purposes remains to be seen. Until then, it is important to use technologies that are already working and, above all, to prevent plastic from entering the environment as much as possible.

Last but not least, it is up to the legislature to ensure that new processes have a chance and that mature ones are used comprehensively as soon as possible. So far, there are no specifications for microplastic emissions in water.

(jl)