On January 17, 2014, ten years ago, a group of Spanish university professors and researchers organized a big event at the Teatro del Barrio, in the center of Madrid, to present a new party. Podemos, this is the name of the party, was a new left-wing formation that had the ambition not only to advance classic demands for social justice, but to radically change Spanish politics. Ten years later we can say that at least in part the intent of those professors and researchers has succeeded: Podemos has changed Spanish politics, even if not with the strength and depth that its founders would have hoped for.

Ten years after its foundation, Podemos has lost much of the revolutionary energy it had at the time, and also from a political point of view it finds itself in the moment of greatest difficulty in its history. Despite this, it is difficult to underestimate his importance for Spanish politics and for the European left, of which he has been one of the most influential and innovative elements of the last decade.

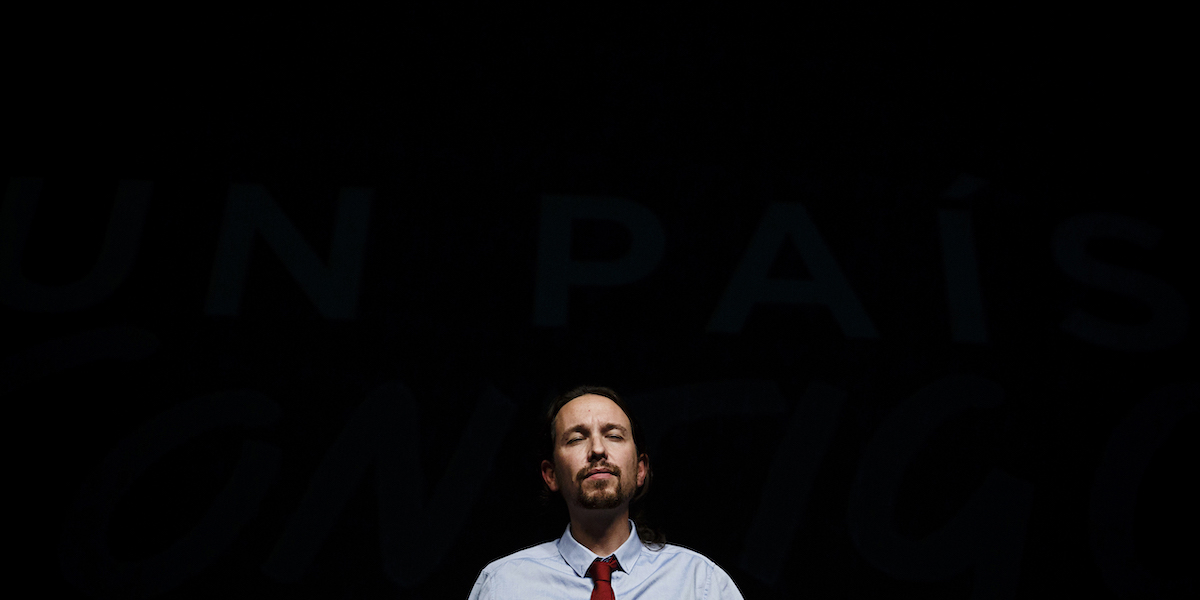

Pablo Iglesias during an election rally in 2015 (AP Photo/Alberto Saiz)

Podemos was born in a very particular moment for Spain. First the global financial crisis of 2008-2009 and then the European sovereign debt crisis of 2011-2012 had left the Spanish economy in terrible conditions, with enormous public debt, high levels of unemployment and an increase in poverty and inequality. The austerity economic policies adopted by the center-right government of Mariano Rajoy’s People’s Party, although they corresponded to those recommended by the international financial institutions, only increased the feeling of anger and helplessness of a significant part of the population.

The economic discontent was combined with political discontent, caused above all by large cases of corruption which had involved the People’s Party itself. In those years, in Spain as in Italy, the traditional political class was defined as “casta” (the word is the same in Spanish) and there was a strong demand for political renewal.

The first reaction to this anger was the 15-M Movement (so called because the first major demonstration was held on May 15, 2011), which is better known in Italy as the movement of Outraged and which was an impressive protest movement against the crisis and against the Spanish political and financial class. But the most important response came a few years later, and was the foundation of Podemos.

Formally Podemos was founded by five people: Pablo Iglesias, Íñigo Errejón, Juan Carlos Monedero, Carolina Bescansa and Luis Alegre. All were professors or researchers of political science, sociology or philosophy at the Complutense University of Madrid, the most important in the city, and all moved within the anti-capitalist and far-left movements active in those years in the academic environment. Pablo Iglesias, who would later become the most well-known and charismatic figure of the party, was already quite well known in Spain, because for about a year he had often been a guest on some television talk shows.

Podemos was formed in a moment of great turmoil for the European left, in which various more or less radical movements and parties were born or established which would later be defined, rightly or wrongly, as “populist”. In 2013, Syriza was founded in Greece, a country experiencing an even more serious economic and political situation than that of Spain. Also in those years, the 5 Star Movement in Italy was experiencing its first major national successes, which over time would move away from the left, but which initially arose from essentially similar social demands and requests.

Pablo Iglesias is part of the leadership of Podemos in 2014 (AP Photo/Daniel Ochoa de Olza)

With the movements of the populist left of the time, Podemos shared some requests linked above all to the renewal of politics and requests for participation from below: as happened in other European countries, the success of Podemos brought a new ruling class into parliament which over time changed many of the ways of doing politics of the traditional parties. In some cases the members of this ruling class were also quite inexperienced.

At the same time, compared to other movements, Podemos rested on a much more solid theoretical basis and became the bearer of some very heartfelt demands which would later become central in the politics of the following years, such as environmentalism and feminism.

Above all, Podemos had the ambitious goal of not limiting itself to representing only far-left voters, but of becoming a mass party, capable of supplanting the Socialist Party (PSOE), the historic party of the Spanish center-left. This objective never really succeeded, but in its years of greatest strength, between 2015 and 2017, it came very close and for a long time the media spoke of the possibility of Podemos “overtaking” the PSOE (the Spanish newspapers actually wrote ” overtaking” in Italianalthough the correct Spanish word would be overtaking).

This ambitious strategy also translated into an aggressive tactic. In his speech presenting Podemos, ten years ago, Pablo Iglesias said: “Heaven is not conquered with consensus, it is conquered with assault.”

Especially in the early years, Podemos used extremely combative political marketing techniques, contributed to stirring up controversy and used social networks very skilfully: in particular Twitter, which became the main means of communication for the party and Iglesias. These tactics contributed to making Podemos extremely popular, but also to giving the party the definitions of “populist” and “anti-system”.

In their own way, both are correct: Podemos, at least at the beginning, was a populist party, that is, demagogic and anti-elitist, and it was also an anti-system party, to the extent that one of its explicit objectives was to profoundly revolutionize the Spanish political class, deemed corrupt and inadequate. Compared to other populist European movements, however, Podemos has always maintained a solidly left-wing soul, and a rather concrete program based on social justice, the reduction of inequalities, feminism, environmentalism.

Podemos ran in the 2014 European elections and obtained a good result: 8 percent of the national vote and five MEPs. From that moment its influence continued to grow, until it became the third Spanish party for years, behind the Popular Party and the PSOE. The greatest electoral success came in the June 2016 elections, when Podemos – in coalition with other left-wing parties and under the name Unidas Podemos – obtained more than 21 percent of the seats and came within less than one percentage point of “overtaking” on the PSOE.

Podemos was also an extremely fractious party: of the five initial founders only two (Iglesias and Monedero) maintained ties to the party, although both withdrew from active politics. In 2019, for example, the exit from the party of Iñigo Errejón, one of the founders and the most important leader after Iglesias, was particularly complicated and stormy.

The political rise of Podemos was also characterized by serious judicial accusations which, however, almost always proved specious. In particular, for years the party leadership was accused of receiving illicit funding from authoritarian governments such as that of Venezuela, but none of these accusations were ever proven to be true.

Podemos’ political decline began with the 2019 elections, when the party – still within the Unidas Podemos coalition – took around 11 percent of the votes. The following year, however, for the first time in its history Podemos managed to enter the government of Spain, thanks to an agreement with the Socialist Party led by Pedro Sánchez. The one between Podemos and PSOE was the first coalition government in the history of Spain, in which Iglesias became vice-president of the government, alongside Sánchez, and Podemos appointed numerous important ministers.

The famous and embarrassed embrace between Sánchez and Iglesias after the closing of the agreement for the formation of a coalition government (AP Photo/Paul White)

From certain points of view, the entry of Podemos into the government was its greatest political success: the Sánchez government with Podemos inside was the most left-wing in Europe, which approved numerous very ambitious economic and social reforms to which the left had been aiming for a long time. At the same time, for many, entry into a coalition government constituted proof of the normalization of Podemos: born with the aim of supplanting the PSOE, the party had become its minority partner.

Staying in government has damaged Podemos from an electoral point of view: with the polls falling, in the 2023 elections Podemos agreed to join Sumar, an electoral cartel created by Labor Minister Yolanda Díaz with the aim of collecting the votes of the formations to the left of the PSOE. Sumar obtained a decent result in the elections, around 12 percent of the votes and 31 deputies. But Podemos collapsed: of Sumar’s 31 deputies, only five seats went to Podemos representatives.

This led to a split between Podemos and the rest of the coalition. The few party deputies left Sumar and the majority, and are currently part of the mixed group. Today the goal of Ione Belarra, the party secretary who replaced Iglesias in 2021, is to re-establish Podemos, and bring it back to its old successes.