Shortly after Alain Tanner and Jean-Luc Godard, another grand master of “radical cinema” died last November: Jean-Marie Straub, who also lived in the Lake Geneva region. Film critic Christopher Small pays tribute to the political activist with the camera and highlights his commitment to the “resistance”.

This content was published on Jun 04, 2023

Christopher Small

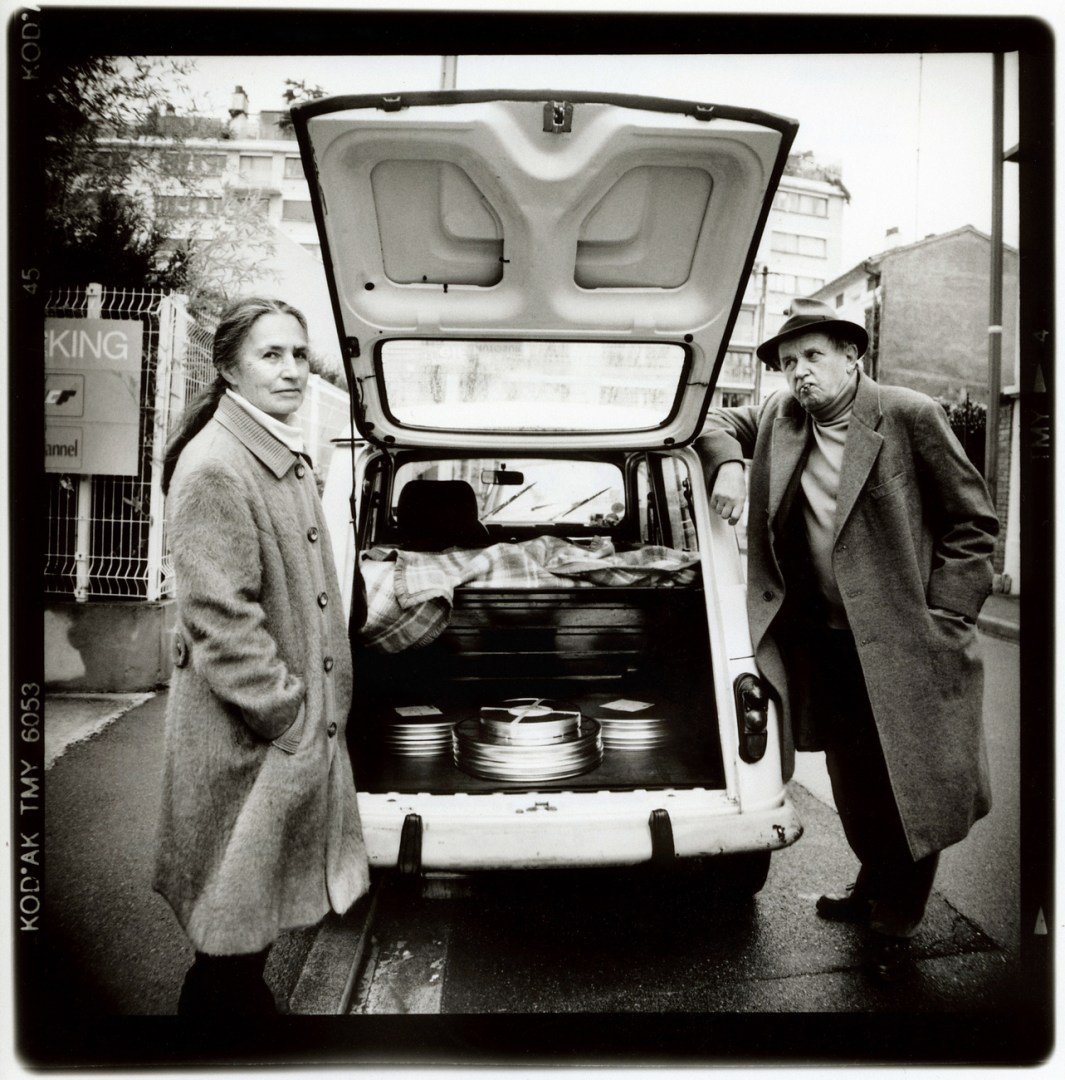

In November, radical filmmaker Jean-Marie Straub, known for his lifelong artistic collaboration with his wife Danièle Huillet (1936-2006), died a few months before his 90th birthday in Rolle.

In its obituary, the French newspaper Le Monde characterized Straub as “Marxist, rebellious, uncompromising, contradictory, stormy and hot-tempered”. Together with Danièle Huillet he has created one of the most unified, poetic and defiantly impenetrable works in film history.

In his final days, Straub would stare from his bed at the autumnal panorama of the French mountains on the other side of Lake Geneva, his companion Barbara Ulrich recalls.

“A permanent cinema,” she called it when I spoke to Ulrich last month as part of the Oberhausen International Short Film Festival, where a homage with four films by Straub was taking place.

As night shrouded the lake in darkness for the last time, Straub stared at the fading colors of the landscape and listened to the beginning of the second movement of Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 12. “I’m sick,” he said, visibly surprised, to Ulrich on the day of his death and took her hand as if realizing his illness for the first time.

In exile

Neither Straub nor Huillet were Swiss. Huillet was born on May 1, 1936 in Paris. Straub was born three years earlier in Metz, a place that was French at the time of his birth, German during the war and became French again on Victory Day (9 May 1945).

This biographical detail clarifies the pan-European character of the films of the two. While only a few works by the Straubs, as the couple were called, can credibly be described as adaptations, they were based on existing texts, almost all of which were penned by Europeans.

Unlike typical screen adaptations, in which the source material is edited or abridged to fit a cinematic narrative, the Straubs sought to transfer the original lyrics to another medium with the utmost care and vigor. They gave the words room to breathe – unforced and unvarnished.

Huillet and Straub met in Paris in 1954, she was 18 and he was 21. In 1958 they fled France for West Germany after what he described as his refusal to take part in the French army’s terrorization of Algeria. The couple lived in exile in Munich for over a decade before moving on to Italy, where they produced films until Danièle’s death.

When his partner died of cancer in October 2006, Straub returned to Paris with Ulrich, where he produced a number of short films and videos over the next few years.

They continued their work in the Tuscan town of Buti. The journeys from Tuscany to Paris led them through Switzerland, where Ulrich, who is a Swiss citizen, had an apartment.

Her stays in Rolle grew longer with each passing year. When Straub’s health no longer permitted extensive travel, they moved permanently to the community in 2015. Four of the last six films he produced with Ulrich were shot on the shores of Lake Geneva.

The relationship with Switzerland

“Switzerland was not terra incognita,” Ulrich told SWI. “In the 1960s, when they were shooting their first films in Munich, they always went to Geneva for subtitling. It was around that time that she met the Swiss film critic and curator Freddy Buache. He always bought copies and showed the films.”

Straub-Huillet’s work has been characterized by intimate and intense working relationships over the almost 45 years they have worked together. Friendship with Freddy Buache, longtime director of the Cinémathèque Suisse (the national film archive), and his tireless support of her work had a crucial influence on Frédéric Maire, current director of the Cinémathèque and former director of the Locarno Film Festival from 2005 to 2009 – the Festival that awarded Straub an honorary Pardo d’Onore in 2017.

Buache screened Straub-Huillet’s first two films, Machorka-Muff (1963) and Not Reconciled (1965), at Maire’s school. He confessed that he understood little about it, but the experience left him with a great fascination: from now on, cinema would become the major part of his life’s work.

Straub’s last films treated Lake Geneva not just as a backdrop, but as a concrete place whose history was to be explored. French critic Serge Daney said Straub-Huillet’s films were about “people who resisted”; a film like “Gens du lac” (2018), the fiftieth film with Straub’s name, is no exception.

Based on the novel by Swiss author Janine Massard, the film tells the story of two fishermen – a son and a father – who transported food and medicine across the lake to occupied France at night during the Second World War. On the way back they smuggled Jews and anti-fascist resistance fighters.

Resistance figures like these were neither honored nor recognized as such until their deaths. They are part of a dark, complicated Swiss history mixed with anti-communism.

Straub’s film not only tells a lot about heroism and resistance, but also about the misfortune, death and violence inherent in this tranquil seascape.

The Catholic Marxist

The same Beethoven string quartet was also heard at Straub’s abdication in the Catholic Church of St. Joseph in Rolle on November 25. Straub’s funeral later took place in Paris on the family grave of his wife Danièle in Saint-Ouen.

His departure in a Catholic church came as a bit of a surprise to me, given that he had been a combative Marxist throughout his adult life. Klaus Volkmer from the Munich Film Museum, a friend of the Straubs, commented that at least the hearse was white and not black.

When I asked Barbara Ulrich about it in Oberhausen, she corrected my mistake. Jean-Marie Straub’s first ideological love affair before communism was Catholicism. He attended a Jesuit high school in Metz and therefore never completely abandoned it.

As ideologies, Straub explained to her, both aim to create “a brave new world” – in one form or another. “And neither works,” added Ulrich.

Tod am See

Straub’s death came just a few months after two other deaths in Switzerland became known that shocked film lovers from all over the world: Alain Tanner, 92 years old, died in Geneva on September 11, 2022, and Jean-Luc Godard, 91 years old , passed away just two days later, also in Rolle, by means of assisted suicide.

Not only have we lost three representatives of the radical 20th century film tradition, but their deaths come in close succession and in remarkably close proximity to each other. Tanner, Straub, and Godard died within months, just a half-hour drive from each other, on the same lake.

Ulrich emphasizes that the connection to Rolle was accidental, but that of course she and Straub considered it a bonus that “these two very different monuments (Godard and Straub)” came together there. “They weren’t small talk men,” she emphasizes. “They only communicated indirectly, through films and gestures”.

Godard had given Straub-Huillet a substantial sum of money in 1967 for her first feature film, The breaking latest news of Anna Magdalena Bach (1968). And he used all his fame to publicly support her films again and again. He recently emphasized: “I don’t think you like many of my films, but I like all of your films”.

Preserve the memory

For a long time, Straub-Huillet’s films were not available on DVD or video. As evidenced by published correspondence with various distributors, film museums and festivals over the decades, Huillet was meticulous and emphatic about the best possible screening conditions.

After her death and as digital transmission techniques improved, her work gradually became available for home use as well.

Ulrich, who was Straub’s partner in the production company Belva-Film, set about preserving and redistributing her work, culminating in an extensive restoration project for almost all of the films. “A crazy undertaking, because we started with nothing,” she explains.

A retrospective of these new digital versions of the films has been shown on arthouse streaming platform MUBI during the pandemic. In recent years she has toured the world, sparking interest in the work of filmmakers long considered marginal, difficult and even outside the art house mainstream.

The original negatives are now safely stored in “old, cold boxes” in France and Switzerland.

In their own words: Straub and Huillet in conversation, filmed by Portuguese director Pedro Costa. This excerpt is part of the short film 6 Bagatelas (Six Bagatelles), which was shot using scenes used in the final version of his documentary about the Straubs, Onde jaz o teu sorriso? (Where’s your smile?), weren’t used.

Translated from English: Michael Heger

In accordance with JTI standards

More: JTI certification from SWI swissinfo.ch