“When Claudio Abbado finishes the rehearsal, we wonder how long it will take for him to leave. But at the end of each concert, we beg you to spend more time with us.”

The phrase, uttered by a horn player from the Berlin Philharmonic – who for obvious reasons did not want to remain anonymous – in the early 2000s, reflects the extreme feelings that the Italian maestro provoked in his subordinates.

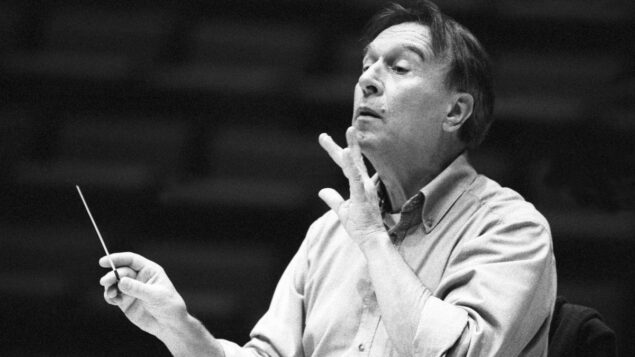

Abbado was a man of few words, and his rehearsals were punctuated by moments of silence. “I prefer to communicate with eyes and hands,” he declared in the documentary Hearing the Silence (2004). Certain conductors burn down a symphony group. Others impose themselves due to the rigor and rigidity of their conduct.

Abbado seduced his followers with his smooth conduct, especially the “drawings” of his left hand, which shaped the melody while with his right he marked the time of the works.

Ten years after his death, few conductors boast such a powerful CV. Abbado was musical director of Milan’s alla Scala in the 1960s and 1970s; he took over – and rejuvenated – the London Symphony in the 1970s and the Vienna State Opera. He also took on the role of principal guest conductor of the Chicago Symphony and was a constant collaborator with the Vienna Philharmonic.

In 1989, he achieved the Holy Grail of conducting: the Berlin Philharmonic chose him to succeed Herbert von Karajan (1908-1989), with whom the orchestra had achieved the status of the best symphonic group in the group. Abbado led the Berliners until 2002.

The maestro’s personal conduct is as important a legacy as his musical contribution.

Born in Milan on June 26, 1933, Abbado was a selfless defender of humanitarian causes from an early age. He witnessed the presence of German officers in his hometown and saw his mother arrested for sheltering a Jewish child.

His contempt for dictatorships was so great that he refused to conduct works by the Italian Otorino Respighi (1879-1936) and the German Carl Orff (1895-1982), given their sympathy for fascism and Nazism.

When he took over at Scala, he joined pianist Maurizio Pollini in the crusade to popularize so-called “classical music”: they played for factory workers and Abbado even made opera house tickets cheaper to attract an audience with lower purchasing power.

In Berlin, he refused to be called “maestro” by the musicians – a demand of the dictator Karajan. “Call me Claudio,” he asked. The democratic stance, in which the regent assumed more of a collaborator position than the imposing figure for which he was feared, opened space for new leadership figures – one of his last patrons was the Venezuelan Gustavo Dudamel, one of the main talents of the current regency .

Abbado had a comprehensive repertoire, with emphasis on interpretations of symphonies by the Austrian Gustav Mahler (1860-1911). But he was a man of his time. In all the groups he directed, he led works by 20th century authors such as Pierre Boulez, Luigi Nono, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Arnold Schoenberg.

When he was in charge of the Vienna Philharmonic, he created Wien Modern, a festival that welcomed new composers. In Berlin, he added works of contemporary music alongside creations from the classical and romantic period (specialties of his predecessor, Karajan) and created a festival dedicated to chamber music. His departure from the orchestra was due, among other things, to poor record sales and because he thought the Berliners should refrain from crossing classical music with rock – but they preferred to disobey their boss and released a controversial album with the group Scorpions.

Claudio Abbado left Berlin in 2002 and began dedicating himself to the Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra, made up of young instrumentalists, and the Lucerne Symphony, a kind of selection of musicians from the main symphonic groups in the world. Diagnosed with stomach cancer, he died on January 20, 2014.

His work remains impeccable.

Sergio Martins