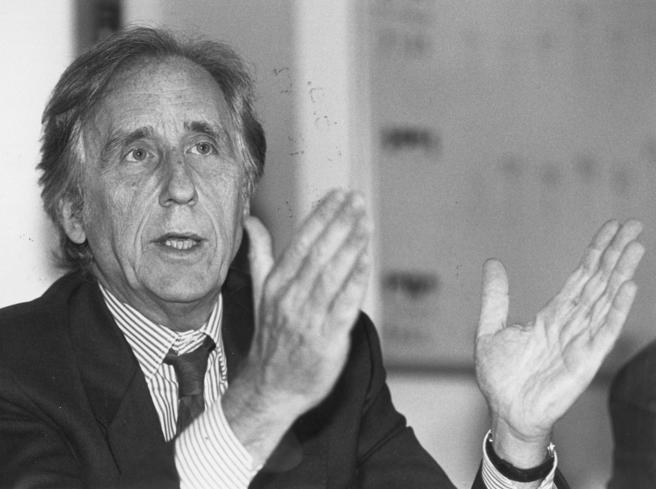

Everything has been said about the disappearance of Giorgio Ruffolo and with the utmost authority. However, I would like to add something that can be useful to remind young people of what economic programs once were and what parties were.

On the economy, we have had an enormous, epochal shift to the right in the world, passing from a substantially Marxist cultural hegemony to a hyper-liberal one. In this context, today it is hard to imagine how “leftist” even firmly pro-Western and pragmatic socialist parties were, such as those of Nenni and Saragat in Italy. At the beginning of the 1960s, when the first centre-left government was formed with the entry of the PSI, Giorgio Ruffolo already had a role as grand commis of the state in planning at the Ministry of the Budget, he was a socialist leader of the so-called left ” Lombardiana“, friend and collaborator of Antonio Giolitti, like him a supporter of Riccardo Lombardi. As a junior journalist for Avanti!, I followed the clash within the party between two editors of the newspaper who succeeded each other (first Pieraccini and then Lombardi) and between two ministers of the budget who also succeeded each other (first Giolitti and then Pieraccini).

As editor of the newspaper, Pieraccini himself, who would move on to become Minister of Public Works after a few weeks in the first centre-left government (and would complete the Milan-Naples) entrusted me with an inquiry into the nascent motorways. Lombardi arrived and blocked me, explaining that they were wrong choices, which favored private transport over public transport: first of all, it was necessary to invest in trains and not in cars.

The clash between Giolitti and Pieraccini told me the latter. In the first centre-left Moro-Nenni government, Giolitti had held the key role of Minister of the Budget, in which he represented Lombardi, who had preferred to become, as we have seen, director of Avanti! instead of Pieraccini. Giolitti supported a program that for simplicity could be defined as “impositional”: five-year plans, that is, rigid, which imposed the choices decided by the government on private investors as well. The Christian Democrats (and the autonomist majority of the PSI) were instead in favor of “proactive” programming, which would direct the choices of private individuals without forcing them towards the established political objectives: above all, the development of the South. Eventually, the break came and, in the second Moro-Nenni government, Pieraccini replaced Giolitti in the Ministry of the Budget.

Today, economic planning no longer exists, it is not even talked about anymore (as, moreover, of the development of the South through investments rather than gifts and “citizen’s income“). On the contrary. There is no longer even an industrial policy. But Lombardi and Giolitti then accused Nenni and Pieraccini of being right-wing.

Ruffolo also reminds us of what the parties were like. Corrado Augias made perhaps the most beautiful and moving commemoration of it in Repubblica, in the title of which we read: “farewell to the ex socialist minister not loved by Craxi”. Frankly, I don’t know if he loved him, but he had some reason for rivalry. Ruffolo was in fact a leading exponent of the “Lombard” current, opponent of Craxi. Eugenio Scalfari was Craxi’s archenemy, but Ruffolo was particularly close to him and in fact remained the most authoritative economic commentator on La Repubblica. In December 1979, with the support above all of Scalfari’s newspaper, the attempt to place Craxi in the minority on the party’s Central Committee and replace him with Giolitti (always the main point of reference for Ruffolo) narrowly failed. I remember it well too, because there was an agreement between the majority and the opposition in the PSI which also envisaged, as part of a rebalancing, kicking me out of Avanti! (which then, I don’t know why, doesn’t happen). Despite all this (and it is no small matter), in 1987 Craxi brought Ruffolo to be a minister in the Goria government (and in a key ministry such as that of the Environment). It seemed normal, because there was democracy in the parties (indeed, internal democracy was inherent in the parties themselves), currents existed, with their different cultures and policies. So that even a strong secretary, like Craxi, had to take this into account, through compromises, searches for balance, checks and balances that followed the clashes. The balance between currents required that there be an exponent of the left in the PSI delegation and Craxi chose Ruffolo (whether he loved him personally or not). Certainly because he knew its indisputable authority and competence. And in fact he confirmed it without discussion in the successive governments of Mita and Andreotti, until 1992. Basically it was the same logic for which in 1978 I became director of Avanti!, but supported by a deputy director of the left of the party: Roberto Villetti, who had to act as a counterweight.

I, too, had some prejudices towards Ruffolo when I began to see him after taking over the leadership of the newspaper. However, I soon began to “love” him for the simple reason, above all, that he was “lovable”: irresistibly likable. We would still have had a constructive relationship, because the prestige of Avanti! he appeared absolute to everyone: it was a party institution, what he asked for was done diligently, even by the most authoritative and famous of professors. Perhaps Ruffolo saw me as a somewhat naïve boy, but I was still the director of Avanti! and he, even though many years older, seemed like a boy in his turn, for the cheerfulness, light-heartedness, the irreverent humor with which, as often happens to people of superior culture, he made difficult things simple.

Of course, the currents of the party also weighed in on the details. Roberto Villetti was from the left like him and therefore relations were first and foremost between the two of them. Among the economists, I rather favored Francesco Forte and the chain of his young students closest to the “liberal socialist” turning point impressed on the party: from Tremonti to Brunetta.

In the special relationship between Roberto Villetti and Ruffolo, on the other hand, the common work in Mondoperaio also weighed, where the former had been deputy director in the 1970s and the latter, with Sylos Labini and others, among the protagonists of an economic and cultural elaboration which left a deep mark.

The decades-long friendship and fraternal collaboration between Villetti and me indicates how militancy in different currents of a party does not necessarily harm personal relationships. And the Ruffolo family also indicates it. He had two older brothers, both protagonists of the Resistance in Nazi-occupied Rome, arrested and miraculously survived. One of them, Sergio, a painter and draftsman, was perhaps the most famous graphic designer of the time, an advertiser, creator, among other things, of the graphic format with which La Repubblica was born in 1976: a tabloid format with a revolutionary modernity. In the last phase of my direction at Avanti!, I wanted to renew its appearance and transfer (it was perhaps the first) the composition of the pages completely on the computer, through a then nascent technology. I spoke about it to Sergio Ruffolo who immediately accepted with enthusiasm to carry out the project, glaring at me at the mere hint that his (enormous) work could be paid for. This is how he was born, in 1987, solemnly presented by Craxi, the Avanti! in its new guise, with the first page in color, short and incisive titles. It wasn’t easy to make it every day: the most beautiful projects tend to deteriorate in practical application. And therefore Sergio Ruffolo, who knew the stickiness of the editorial offices, stayed with us for months, with pitchfork and rifle to get the best out of his extraordinarily innovative project (perhaps-he thought-innovative like that of Repubblica ten years earlier).

After such a long time, certainly the positions mentioned above on the economy of the 1960s by Lombardi, Giolitti and Ruffolo may appear even more extremist than they already appeared to us autonomists then. But you can also do some self-criticism. The Lombardians, driven by idealism and political passion, were not just dreamers. They saw, perhaps too early, the disasters that would derive (also for the maintenance of democracy in the West) from the unbridled Anglo-Saxon liberalism transformed into an ideology. They saw the environmental risks, because private motorization has certainly been a conquest, but if we had developed the subways in time, the transport of heavy loads by train and small coastal vessels along the coast, CO2 emissions would be more tolerable. They saw the role of public industry, because in Italy, not by chance, beyond a certain size, we only have this one left. And small or medium-sized enterprises, while typical of our extraordinary vitality, are not enough.

Giorgio Ruffolo’s life span was long, almost a century. And even his story therefore serves to understand the past, contrasting clichés that do not help us build the future.

George Ruffolo. A memory of Ugo Intini – working world

124

previous post