Listen to the audio version of the article

Despite the popularity of literary recipes, we do not recommend repeating that of the cutlets loved by Gogol and told in an extraordinary book, Nikolai Gogol’ in the memories of those who knew him (Quodlibet), translated and edited by Giovanni Maccari. The Ukrainian writer was a gourmet and during a trip with some friends in October 1839, he insisted that they keep their stomachs empty until they reached Torzhok, where they ate delicious breaded cutlets. The leg of the journey took longer than expected due to the tiredness of the horses and so dinner was skipped.

In the morning the group finally arrived in Torzhok, about two hundred and fifty kilometers from Moscow, and ordered the legendary cutlets. They were actually very good. Except that long blonde curls began to emerge from the breading. The misadventure, which Gogol joked about according to his grotesque taste, generated a fit of hilarity among his traveling companions: “We were laughing so hard that the cook and our servant looked at us with their eyes wide in amazement”, writes Sergei Aksakov. “Eventually the fit of laughter subsided. Vera ordered some broth to be heated for her while the three of us manfully tackled the cutlets, after avoiding all the hair.”

The oddities

That “manly” conveys the idea in a priceless way. The man must sacrifice himself, while the cook justifies himself by claiming, as Gogol predicted, that the hair was chicken “hair”, while it was clear that it was his. Gogol was loved by his friends and the public but also the victim of misunderstandings due to the oddities that characterized him. His works, although highly successful, were often not understood and many simply dismissed them as comical. And even his love for Italy was viewed with suspicion by the patriots who thought it was inappropriate for such an illustrious subject of the Tsar to spend so much time in Rome and return full of the desire to return (as well as supplies of pasta and parmesan to prepare the macaroni to friends). At that time an author did not live from the publishing market, even if he earned money from books, theatrical performances and articles in literary magazines. The bourgeois humus in which the novel genre would flourish had not yet formed in Russia and the writers were often aristocrats. Belonging to the nobility did not always mean being rich enough to live without working in St. Petersburg or Moscow. Gogol could devote himself to letters without material worries thanks to loans and the hospitality of families who had palaces, servants and mountains of rubles. Nikolaj Berg, another acquaintance, tells how the writer was looked after and protected during his stay in Moscow by Count Tolstoy, the writer’s namesake. Gogol’s servant was Semyon, a Ukrainian, very devoted to him. No one had the right to disturb him, but this ideal condition ended up harming creativity. Gogol didn’t like to talk about his work and if they asked him questions he would change the subject. But on one occasion, Berg says, he responded to those who asked him why he hadn’t written much lately. Gogol responded with an Italian memory. While he was traveling between Genzano and Albano he had stopped in a popular restaurant full of dust and noise: “At that time I was writing the first volume of Dead Souls and I never separated from the notebook. I don’t know why, the moment I entered the restaurant I felt like writing. I took a table, sat down in a corner, took out my bag and despite the rolling of the balls on the billiard table, the incredible noise, the coming and going of the waiter, the smoke, the suffocating heat, I sank into a sort of dream and wrote a chapter whole without raising your head. Those pages still seem to me to be among the most inspired I’ve ever written.”

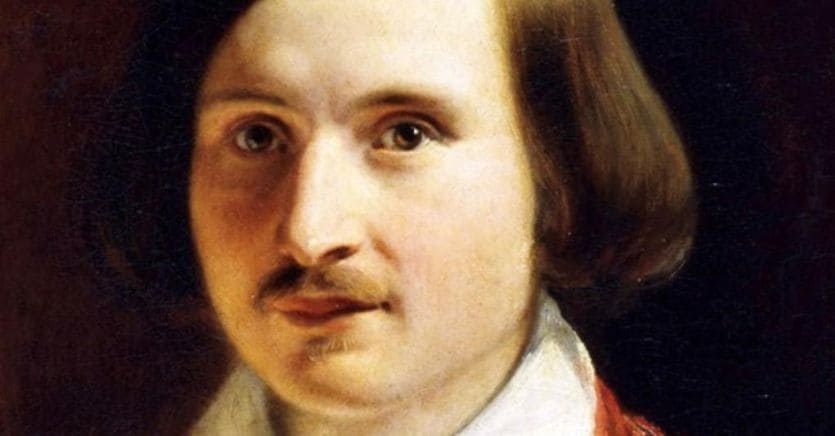

“Typical Ukrainian look”

One thing that is striking about reading the testimonies is how much Gogol was seen as Ukrainian: he had a “typical Ukrainian appearance”, a “typical Ukrainian cunning”, a “typical Ukrainian humor”. When he was in a mood he sang Ukrainian songs on the street. Shy and full of oddities since he was a boy, often unfriendly, he could be extraordinarily histrionic and affable. Especially him if he met a Ukrainian. In other words, the great season of the Russian novel was born in the wake of a “little Russian”, as Ukrainians were called at the time. “We have all emerged from Gogol’s Coat,” Dostoevsky is said to have said (he might well have said from the Nose, but he might have sounded unseemly).

Gogol’s first successful book, The Vigils on the Farm near Dikanka, draws heavily on Ukrainian folklore, although it is not generally included among the author’s great works. Even Dead Souls, according to some scholars, could be set in Ukraine, more precisely in the Poltava governorate, approximately halfway between Kiev and Khark’iv, in the places where the writer was born and raised. But this is a hypothesis that makes little sense because Gogol makes it a paradigmatic place for the entire empire. What is certain is that his revolt against the oppressive and castrating modernity represented by the city of St. Petersburg finds a counterpart in a Cossack society, free and atavistic, like that of the ancient Ukrainian past, idealized and never existed as he thought. When he resigned from the university, where he had found a job as an unlikely history professor, thanks to Pushkin, he said: “I feel as free as a Cossack.” If Gogol was considered a gourmet, in the last phase of his life he refused to eat or had intestinal problems such that he was unable to do so, and he died under the helpless eyes of his friends and doctors who tried everything to take him away from death. Including tormenting him by applying leeches to his nose. The hypothesis of final anorexia is supported by the mystical drift of recent years. Upon returning from a disappointing trip to the Holy Land, Gogol was in a creative crisis because, on a terminal theological wave, he had taken it into his head to give a sequel to Dead Souls according to a Dante’s score. He had described hell, purgatory and paradise remained to be written. But the Middle Ages had long since ended even in Russia and his vein of devastating satire hardly suited the project. The few pages of the second book that survived the stove confirm this. The career of one of the greatest writers began by throwing a book into the stove – all copies of a bad historical novel in the Walter Scott style – and ended the same way.

To end with a happier thought, it is better to remember him preparing žžënka, a legendary and now obsolete convivial cocktail made with rum, cognac and a sugar cube soaked in alcohol and set on fire. Gogol was considered a master and often prepared it to spark conversation and spark joy after lunch.