India’s current population of 1.4 billion people continues to grow, even if the birth rate is now falling somewhat. In these months, its population will overtake that of China.

But with it, the economy is also growing – currently at five to seven percent per year – and CO₂ emissions. However, energy economists know that economic growth is far more relevant to rising emissions than population growth.

Today, India alone generates 70 percent of its electricity needs from coal-fired power plants. According to Our World in Data, almost 30 million Indians still have no access to electricity, and many cannot afford electricity prices.

CO₂ emissions: India ranks third in the world

“Without India, the goals of the Paris climate agreement cannot be met globally,” Miriam Prys-Hansen from the Leibniz Institute for Global and Regional Studies (GIGA) in Hamburg is convinced. But she also sees great opportunities: “The country can positively influence new technological standards, but also prices for existing climate-friendly technologies – such as solar panels, LED lamps or climate-friendly heating systems – simply through the sheer size of its domestic market.”

With CO₂ emissions of 2.7 billion tons per year, the country currently ranks third worldwide behind China with 11.5 billion and the USA with five billion tons of CO₂ per year.

However: Converted to the inhabitants, that is just 1.9 tons of CO₂ per capita and year. China, on the other hand, with 8.5 tons per inhabitant has already overtaken Germany with eight tons – whereby a large part of the emissions has to be attributed to pure export production.

The Indian government has quite ambitious goals because they want the subcontinent to be climate-neutral by 2070. In a first step, at least 500 gigawatts of renewable energy systems should be installed by 2030. For Aniruddh Mohan, scientist at Princeton University’s Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment, this expansion should only cover the increasing demand for growth and thus not reduce CO₂ emissions.

Ambitious expansion goals in India

Mohan also doubts whether the expansion targets are really realistic: “In 2014, Prime Minister Narendra Modi set the goal of installing at least 175 gigawatts of renewable energy by 2022, of which 100 gigawatts will be solar and 60 gigawatts of wind energy. India’s target is around 30 percent missed.” In order to still achieve the expansion target by 2030, the capacity would have to be tripled in less than seven years.

The problem with this is that land is becoming scarce, as Mohan explains: “The best locations have already been taken and buying new land is becoming increasingly difficult.” Photovoltaic systems in particular need a lot of space. Wind turbines would be more space-saving, but there are only a few areas where the wind blows reliably.

In the summer of 2022, the G7 countries launched the “Just Energy Transition Partnership” initiative, which South Africa, Indonesia and Vietnam have joined so far. Though invited to join, India is struggling to do the same. Because its coal-fired power plants are still relatively young, averaging ten years old. “Therefore, it will take huge political and financial capital to shut them down before the end of their planned 40-year lifetime,” says Mohan.

However, Miriam Prys-Hansen doubts whether international cooperation initiatives such as the “Just Energy Transition Partnership” or the “Indo-German Partnership for Green and Sustainable Development” are effective. “Plans developed from outside will be of little use here and will not be politically enforceable, also because of the political climate in India,” she says. “For example, it is estimated that over 21 million people are employed in the fossil fuel sector in India, the majority of them in the informal sector.”

Overcome immense poverty

In addition to its energy problem, India also has a great deal of catching up to do in order to overcome immense poverty and at least create modest prosperity for the poorest. Tilman Altenburg from the German Institute of Development and Sustainability (IDOS) in Bonn points this out. Half of the 1.4 billion Indians live on less than four US dollars a day.

“Decoupling high economic and population growth in India from carbon emissions will take longer than in richer countries, including China,” he says.

In a publication, Siddharth Sareen and Shayan Shokrgoza from the Universities of Bergen and Stavanger in Norway criticize the technical solutions planned so far for the Indian energy problem. Thus, neediness and energy insecurity have increased in the communities where solar mega-projects have been built. Decentralized energy systems are therefore essential for comprehensive access to clean energy, but they have hardly been considered in the plans so far.

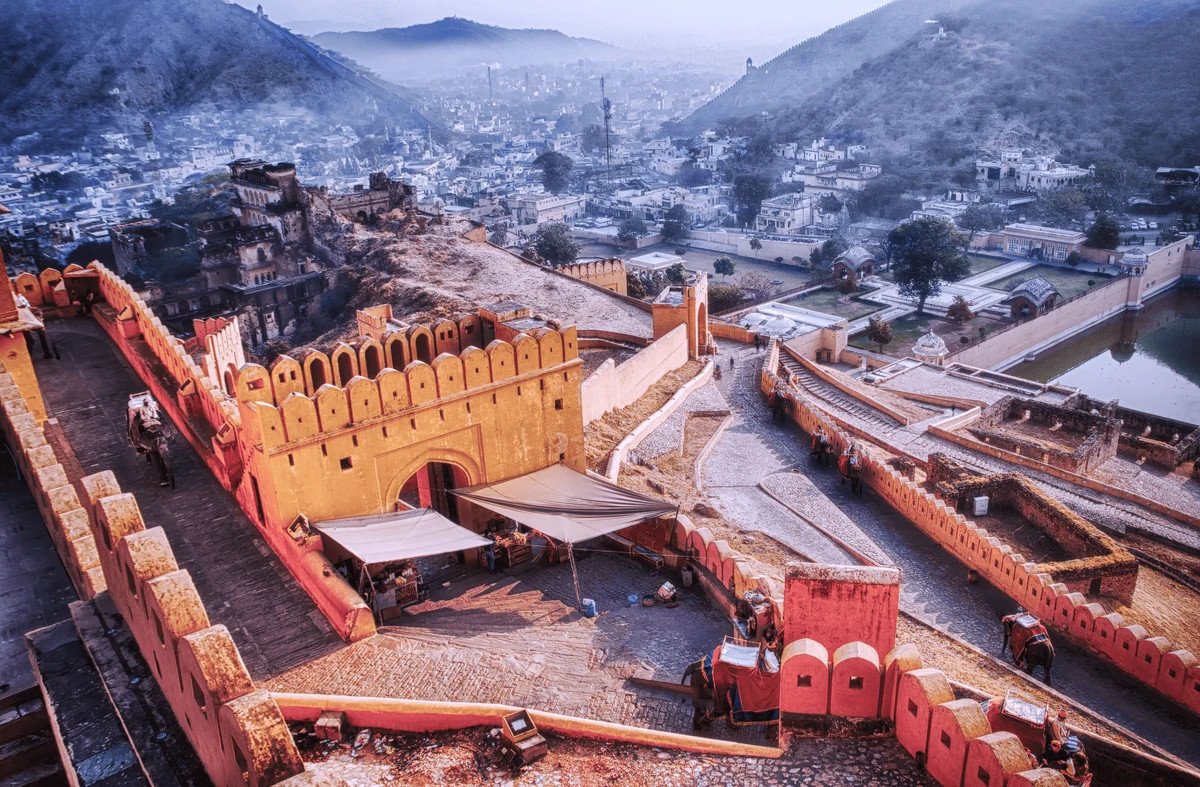

Using the example of the 53 square kilometer Pavagada solar park in the southern Indian state of Karnataka, one of the largest in the world, researchers from the University of Sydney and the Technical University of Sydney led by Gareth Bryant demonstrated that large regenerative systems worsen people’s social situation. Here the areas were not bought, but only leased in order to ensure the owners regular income in the future.

But more than half of the 10,000 people in the five villages near the park are landless farm workers who do not earn any income from the leasehold model. They lost their livelihood. A report by the World Bank warned of precisely this before construction began.

(jl)