Flawless skin, big eyes, narrow nose, full lips, accentuated cheekbones – that is often the basic recipe for the filters, including the currently much-discussed TikTok filter “Bold Glamour”. He seems to have taken fake beauty to the extreme in augmented reality (AR). The algorithms create a smooth image that also reacts to abrupt head movements and facial movements.

Veronica started filtering her selfies on social media when she was 14. Everyone at her school had fun playing with it, she recalls: “It was kind of a joke. People didn’t care about looking good.”

“We do,” says her younger sister Sophia, who was in fifth grade at the time. “12 year old girls having access to something that doesn’t make them look 12? That’s the coolest thing ever. It makes you feel so pretty.”

Face filter as a virtual dress-up game

When augmented reality face filters first appeared on social platforms, they were a gimmick, a kind of virtual dress-up game to look like an animal or suddenly grow a mustache. Today, however, especially teenage girls want to use such filters to beautify their appearance by sharpening, slimming or recoloring face and body parts. Veronica and Sophia are both avid users of Snapchat, Instagram, and TikTok, where millions of other people also use filters like this. They allow them to swipe through different identities.

This article first appeared online on August 5, 2021. In connection with the discussion about the current TikTok filter “Bold Glamour”, we are republishing the online text here.

Veronica, now 19, scrolls back to old pictures on her iPhone. “Oh yeah… I was definitely trying to look good here,” she says, showing me a glamor version of herself — seductive, with wide open eyes, slightly parted lips, and tanned skin that looks airbrushed . “This is me at 14,” she says. She seems disturbed by the picture. Still, Veronica says, she uses filters almost every day. “When I’m not wearing makeup or don’t feel like I’m looking my best, the beauty filter can correct certain things.”

Such face filters are probably the most widespread application of AR. Researchers don’t yet understand its effects, but they think they know there are real risks — and that it’s young girls who are particularly at risk. They are subjects in an experiment designed to show how technology affects our identity, self-expression and relationships. And all this without supervision.

This article is from the 5/2021 issue of Technology Review. The magazine will be available in stores and directly from the heise shop from July 8th, 2021. Highlights from the magazine:

With beauty filters, the software recognizes a face and overlays it with an invisible template made up of dozens of points, forming a kind of topographical mesh. A whole universe of fantastic graphics can be layered on top of this – from a different eye color to attached devil horns, depending on the rules the creators of the filter set for it. Thanks to neural networks, this even works in real time on videos. Jeremy Bailenson, founding director of Stanford University’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab and a luminary in virtual reality research, considers this a masterpiece: “It’s difficult to do it technically.”

These video filters have their roots in the Japanese selfie and “kawaii” culture, which is obsessed with (typically girly) cuteness. Selfies became a mass phenomenon in Japan in the mid-1990s, when photo booths, where customers could decorate their self-portraits, became a staple of arcades. The rise of MySpace and Facebook in the early 2000s then spread selfies around the world. The next stage began with Snapchat in 2011: The app made selfies the ideal medium for visually communicating one’s own reactions, feelings and moods. In 2015, Snapchat acquired Ukrainian company Looksery and released its Lenses feature, much to the delight of Veronica’s school gang.

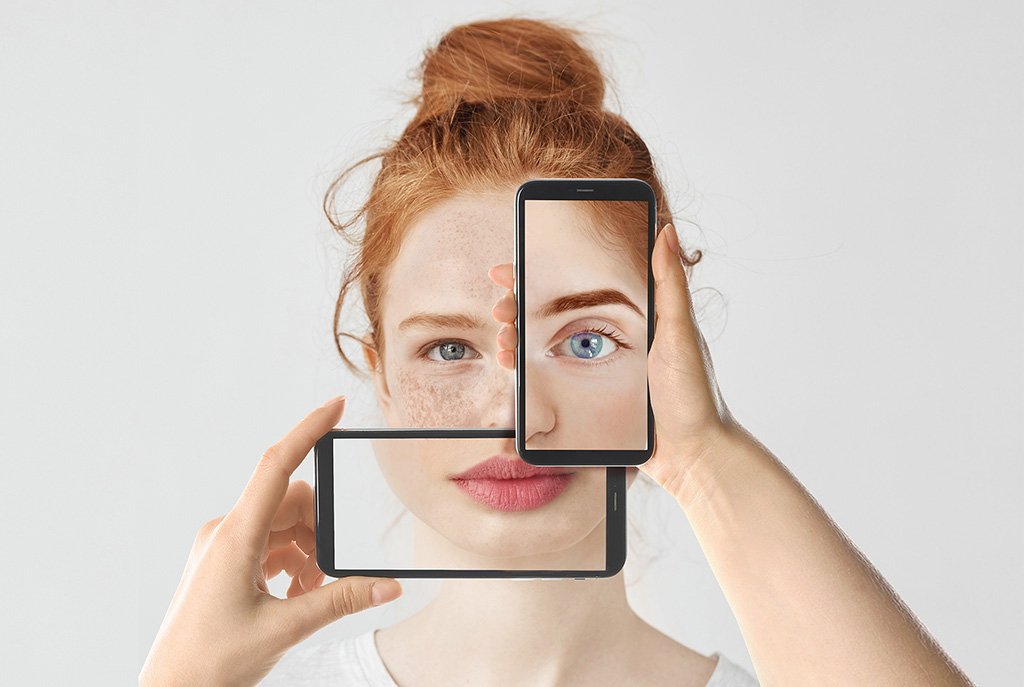

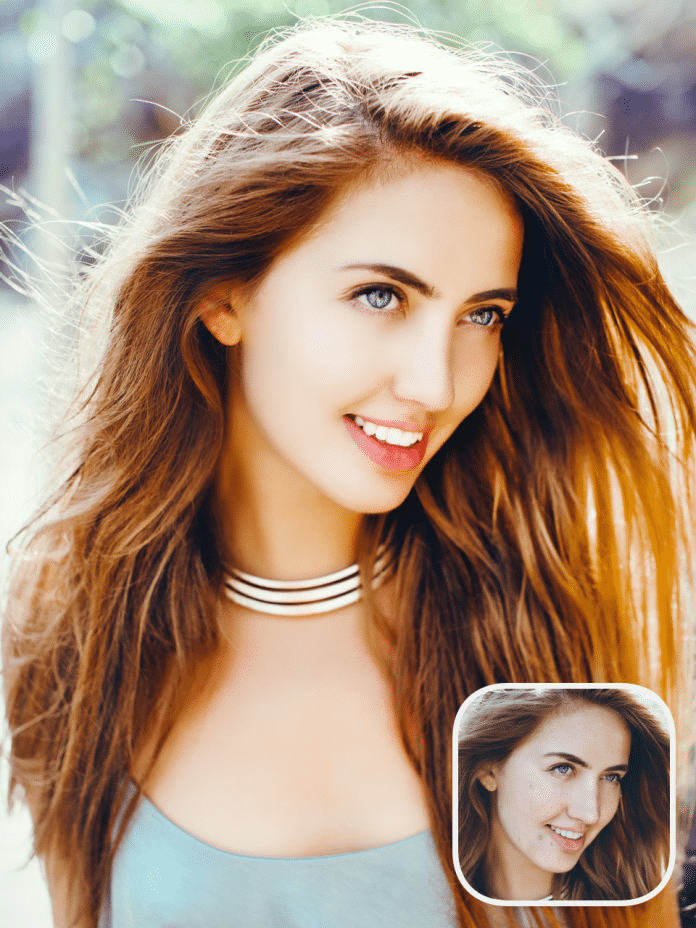

Facetune Filter: The small images show the original photo. After the filter treatment, normal teenagers see…

(Image: Facetune)

Beauty filters in numbers

Snapchat speaks of “200 million daily active users” of Lenses (as of 2021). More than 90 percent of young people in the US, France and the UK would use the company’s AR products. And Facebook (today: Meta) and Instagram report that over 600 million people have used at least one of their AR effects. Almost a fifth of Facebook employees — about 10,000 people — work on AR or VR products, according to Bloomberg. However, most of the filters themselves are created by third parties through an open interface. In the first year, more than 400,000 developers published a total of over 1.2 million effects on Facebook products. As of September 2020, more than 150 creator accounts had each passed the 1 billion view milestone.

For makeup artist and photographer Caroline Rocha, Instagram filters in particular offered a lifeline at a pivotal moment in her life. In 2018, she found herself at a personal low: someone close to her heart had died, and then she suffered a stroke that left one leg temporarily paralyzed and one hand permanently paralyzed. Things became so unbearable that she attempted suicide.

… look like models on the cover of a TV magazine – smooth skin, sparkling white teeth, perfect lighting.

(Image: Facetune)

“I just wanted to get out of my reality,” she says. “My reality was dark. It was deep. I spent my days between four walls.” The filters felt like a breakout. They gave her the opportunity to “travel, experiment, test makeup or try on jewelry,” she says. “That opened a big window for me.”

Rocha studied art history and Instagram filters felt like a deeply human and artistic world full of possibilities. She made friends with AR creators whose aesthetic appealed to her. Discussing various filters for a growing number of followers, she became a “filter influencer” as a result, although she hates the term.