We all run the great risk of ending up in the vortex of “compulsive excessive consumption”. Of dopamine, a neurotransmitter whose release fuels our motivation to action. Anna Lembke is a psychiatrist at Stanford University and director of the Stanford Addiction Medicine Dual Diagnosis Clinic, where he treats people with behavioral and substance use addictions and co-occurring psychiatric disorders. Among his works, the essay “The age of dopamine“ (Roi Edizioni) which has had excellent success in Italy, confirming the interest in this problem. In addition to reporting stories and emblematic conversations taken from her clinical cases, Lembke explores all those complex mechanisms that make us capitulate in the face of obtaining pleasure and which today, the psychiatrist claims, are heavily altered by the environment in which they live. Lembke writes: “Our brains did not evolve to function in this world of abundance. As Tom Finucane, who studies diabetes that develops following a certain type of diet associated with chronic sedentary lifestyle, observed: We are cacti in the rainforest. And like cacti adapted to the arid climate, we are drowning in dopamine.” We asked her a few questions to understand what the mechanisms behind this phenomenon are since their knowledge can be helpful.

Let’s define addiction. Is it possible to draw a clear distinction between unwanted behavior and pathological behavior, looking only at the functioning of the subject in society and suspending moral and cultural judgments?

Certainly cultural norms influence what we consider desirable or undesirable behavior, yet often what is not desirable is not even good for us as individuals or as a community, and therefore we consider it pathological. Rather than think of these two distinct categories, I suggest thinking of them as a spectrum. We all, to some extent, engage in behaviors that are undesirable, both from the perspective of the individual and society. But we are not robots, it is in our nature to push the limits, experiment and sometimes go too far. Most of us can self-correct, but some find it more difficult and there are also those who, while wanting to change an unwanted behavior, are unable to do so without the help of others or without a radical change in the external environment. This is what we call addiction.

The world offers us a universe of possibilities. But some substances are more dangerous than others, just measure some objective parameters. Nicotine increases basal dopamine production in the brain by 150%, cocaine by 225%, amphetamine by 1000%.

These experiments were conducted on rats, not humans, so caution is needed. They also don’t take “drug of choice” into account: what may release a lot of dopamine in one person’s brain may not do so in another’s brain. Interindividual differences are such that not even neurotoxic substances, which are generally intoxicating for most people, are universally intoxicating. Not everyone who drinks alcohol or uses opioids gets “high.” The same person who has little or no positive response to alcohol or other drugs may become very high from gambling, sex, or eating sweets. I have had patients who were so addicted to sugar that when they saw the cupcakes they broke out in cold sweats due to overwhelming cravings.

In Italy, there is fear of the arrival of fentanyl.

Fentanyl is so dangerous because the amount needed to feel high is very close to the lethal amount. Additionally, in the United States, fentanyl is often cut into other drugs, including counterfeit pills. So, some people die from fentanyl because they don’t know they’re ingesting it.

Are we more vulnerable to the lure of drugs today? If yes, why?

Yes, we are. And, as the title “The Age of Dopamine” says, we now live in an era of easy access to substances and behaviors with a high risk of inducing addiction, including substances that did not exist before, such as foods high in sugar, fat and salt and the digital world. This makes us all more vulnerable.

How has the pandemic affected you?

With Covid, we saw a bimodal distribution. Some patients have improved and benefited from a quieter, slower lifestyle to recover from addiction. Others, especially those living in isolation or in dysfunctional families, have experienced worsening addiction. Almost everyone has become a little more dependent on screens and digital media.

What are the other reasons for this greater vulnerability?

Greater access to substances and their effectiveness, free time, boredom and disposable income, even for the poorest of the poor, who today have more money for leisure goods than at any time in human history; and a decrease in the connection between human beings, the meaning of life and the relief of spirituality.

Can self-awareness and knowledge of how certain mechanisms work help us not to be slaves to them?

By realizing that our ancient wiring is not adequate for our modern ecosystem, we can begin to think about how to moderate consumption and even seek pain to restore healthier brain reward pathways.

To re-establish the functioning of the system, avoiding the risk of neuroadaptation, she suggests imposing self-limits and “pressing the pause button” between desire and action. Is such a self-imposed “dopamine fast” always possible?

No, for people with the most severe forms of drug and alcohol addiction, moderation may not be an option. But all the others, for those with milder forms of addiction, are possible. For people with food, sex, and technology addictions, all of us to some extent, it is not possible to eliminate those things from our lives. Therefore, learning moderation is essential. You should start with a four-week abstinence period. For things like food, sex, and technology, that means eliminating problematic behaviors within those categories, rather than giving them up altogether. For example, eliminating sugar, orgasms or Tik Tok/Youtube for four weeks. While four weeks is the average time it takes to begin restoring reward pathways, this is not enough for everyone, in which case longer periods of abstinence will be necessary. Some people may need to eliminate these behaviors from their lives forever.

Continuously bombarded with high levels of dopamine, is our reward system poorly regulated?

I believe that most people living in wealthy nations have changed their hedonic/happiness standard, such that they need more powerful pleasures to experience anything close to pleasure. To the point that when we are not using our drug of choice, we experience some measure of mental and/or physical pain.

Does this increase, in a vicious circle, the risk of moving on to even more potent sources of dopamine?

Yes. With a hedonic reference point shifted to the side of pain, we need pleasures that are more powerful and for longer

Among the risk factors for addiction, you mention poverty, unemployment, multigenerational trauma.

These are well-known risk factors for addiction and other forms of psychopathology. But almost no one has paid attention to the risk factor that has become our modern ecosystem of overwhelming overabundance, in which almost every aspect of modern life has been somehow narcotized, such that even when we have money, privilege, friends and meaningful work and no trauma, we are still vulnerable to addiction.

Lembke concludes his “The Age of Dopamine” with a wish: «We all want to take a respite from the world, a break from the impossible standards we often place on ourselves and others. It is more than natural to try to guarantee ourselves a moment of respite from our incessant ruminations.” To do this, we repeatedly press the dopamine release button. «What if instead of seeking oblivion by fleeing from the world we turned towards it? What if instead of leaving the world behind, we immersed ourselves in it?».

The issue of VITA magazine dedicated to substance use, particularly by young people, entitled “Drugs, let’s open our eyes”, is available here.

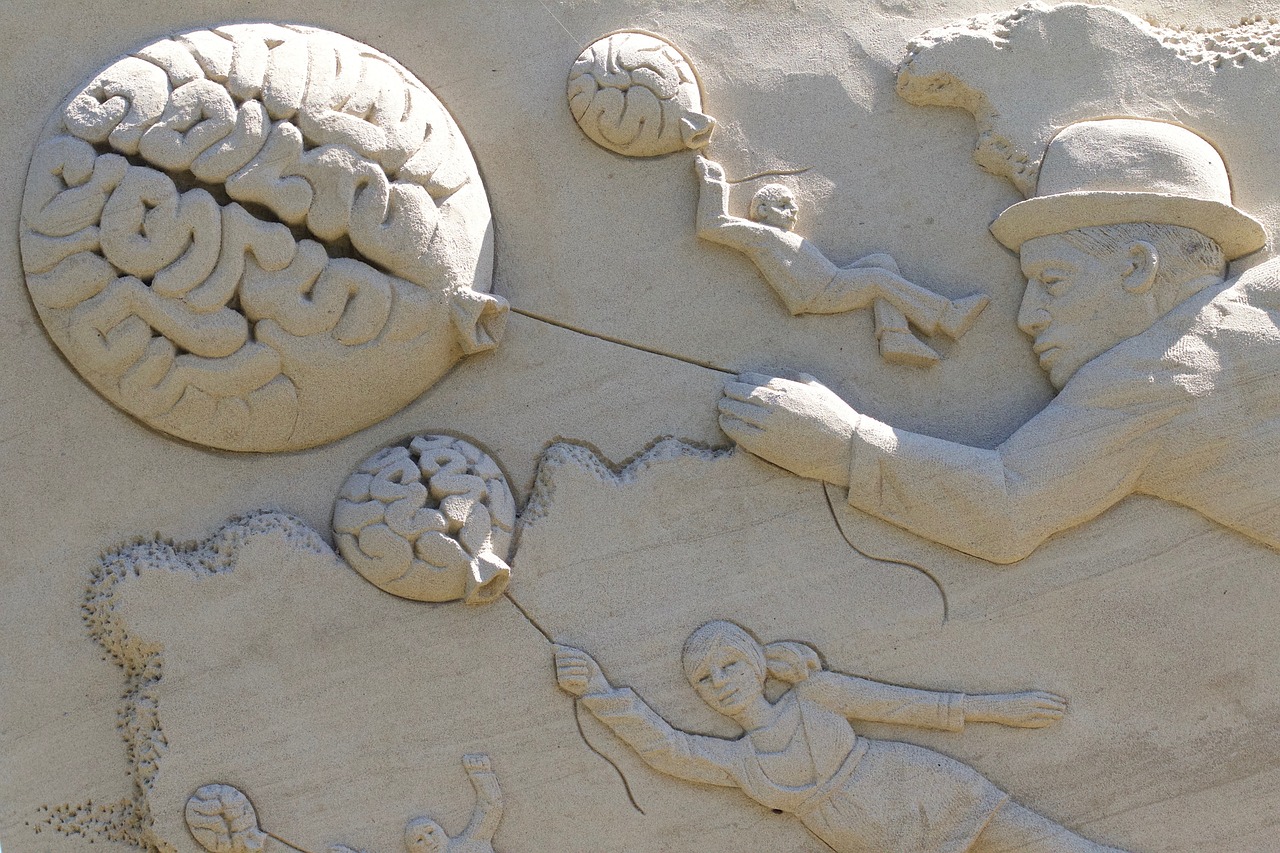

Image by HB from Pixabay