A little fat is ok. If the liver, as the central organ of carbohydrate and fat metabolism, has to store more fat than it can break down, it is called fatty liver. 30 percent of the modern population is affected by this so-called steatosis. “And as the number of overweight people increases, so does the number of our patients,” warns Prof. Dr. Andreas Geier, head of hepatology at the Würzburg University Hospital (UKW). One in five people with fatty liver disease develops fatty liver hepatitis. The inflammation can lead to severe scarring – fibrosis and cirrhosis – as well as cancer. But not only environmental factors such as overeating and lack of exercise, but also genetic predispositions can cause fatty liver disease.

DNA from 10,000 ancient and modern humans analyzed

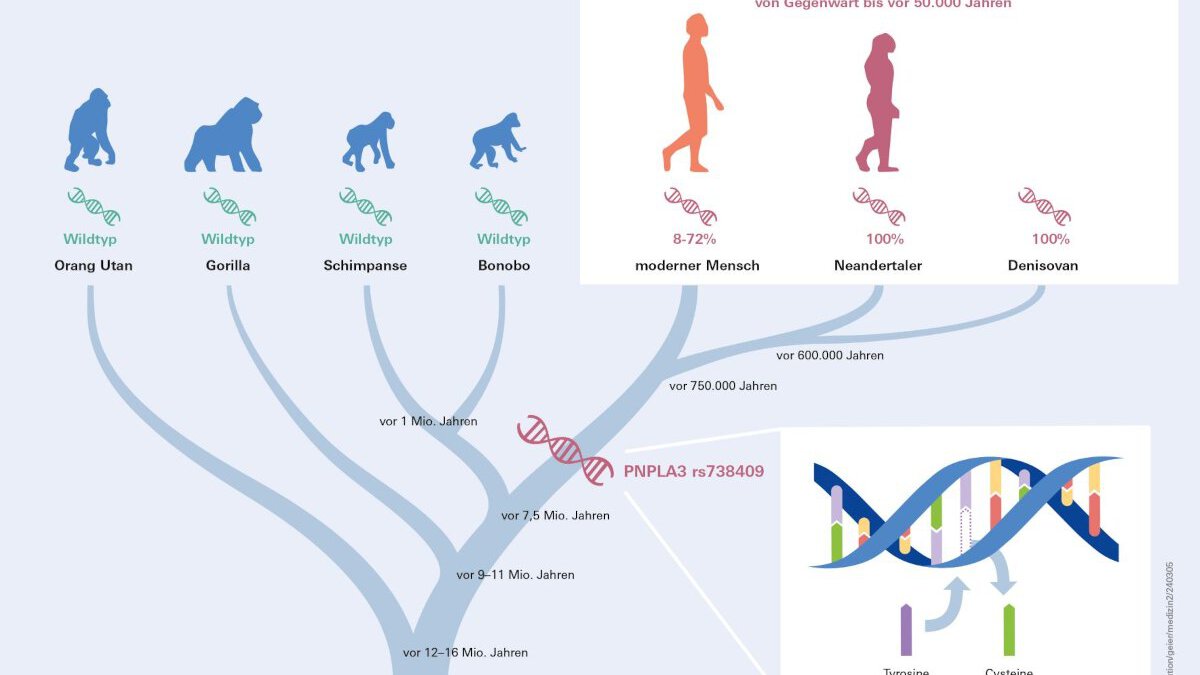

The common variant rs738409 of the PNPLA3 gene plays a well-known and relevant role in the development of fatty liver disease. While the variant occurs rarely in African countries – in Kenya the frequency is 8 percent – in Mesoamerica around 70 percent carry the risk allele, with Peru leading the way with 72 percent. How does this strikingly heterogeneous global presence of the risk allele come about? What is the origin of the PNPLA3 variant rs738409? These questions had been bothering Andreas Geier, who was interested in anthropology, for a long time. He contacted Prof. Dr. Svante Pääbo from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig (MPI-EVA), who was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2022 for sequencing the Neanderthal genome. Pääbo established contact with the Archaeogenetics Department, whose director, Prof. Dr. Johannes Krause, the first genetic proof of a Denisovan human was achieved. Denisovans lived around 40,000 years ago in the Siberian Altai Mountains and are considered the third population of the Homo genus alongside Homo sapiens and Neanderthals.

Together with Stephan Schiffels, head of the population genetics working group at the MPI-EVA, Prof. Dr. Marcin Krawczyk from the UKS and his doctoral student Jonas Trost, Andreas Geier analyzed the DNA of more than 10,000 archaic and modern people from all over the world. These include all 21 available Neanderthal genomes and two Denisovan genomes, as well as the world‘s only hybrid, the prehistoric child with a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father.

Primates carry wild type, early humans carry 100% risk allele

“Surprisingly, all archaic humans who lived between 40,000 and 65,000 years ago carried exclusively the risk allele, which suggests that the variant allele was fixed in their common ancestors,” explains Andreas Geier, going even further back in the human family tree. “When analyzing the reference genome sequence of primates, it became clear that great apes, from the orangutan to the gorilla to the chimpanzee and the bonobo, carry an original, less risky gene variant, a so-called wild type.”

Fat storage once ensured survival

From this, the scientists conclude that the main variant of the fatty liver gene PNPLA3 must have emerged before the human family tree split more than 700,000 years ago. But why? Finally, this variant has unfavorable effects on human health. One hypothesis is that these and other gene variants involved in metabolism evolved in the Paleolithic period to ensure survival. “In particular, the ability to store fat was probably an advantage throughout most of human history, while it is a disadvantage under today’s living conditions,” explains Andreas Geier, using for comparison the habitus of geese, which develop a fatty liver before long-distance flights eat in order to have enough energy on board.

Does PNPLA3 support thermogenesis?

PNPLA3 is also expressed in the retina. Here it is involved in the metabolism of vitamin A, which influences vision at dusk – possibly an important aspect when hunting. It is also found in brown fatty tissue. “Our observation could underline the advantage of fat storage in cold climates and especially for Neanderthals under ice age conditions,” speculates Geier. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that the PNPLA3 variant is prevalent in 89.3 percent of the Yakut population in the coldest region in northeastern Russia. According to Geier, further investigations into the function of PNPLA3 in heat production outside the liver would be exciting.

No significant signal for natural negative selection

The question of natural selection is also interesting. Allele frequencies around the globe have changed little in the past 15,000 years. There is no significant evidence of genetic selection in the archaeogenetic data set. Doesn’t this contradict the hypothesis of natural selection in the Paleolithic? Stephan Schiffels advises caution: “Although our genome-wide analysis did not find any significant signals of natural selection in the last 10,000 years, there is still the possibility that selection was active in periods older than those that we can statistically analyze today “. Given the limited lifespan of archaic humans, it is not surprising that no signal towards negative selection could be found, as this variant probably only develops its adverse effects in later adulthood and is therefore less likely to influence reproductive dynamics.

Did we inherit the fatty liver gene from Neanderthals?

According to Andreas Geier, whether we humans inherited the PNPLA3 variant rs738409 from Neanderthals is the most obvious question that arises from the study, and it is not entirely unfounded. The gene variant SLC16A11, which leads, among other things, to diabetes mellitus, was transmitted from Neanderthals to modern humans, but not to everyone. Homo neanderthalensis was already living in Europe when Homo sapiens came from Africa and gene exchange took place. SLC16A11 is not found in Africa, but variants of PNPLA3 are. And that speaks against gene transfer by Neanderthals. “Although he could have contributed to it,” adds Stephan Schiffels. “In fact, our subsequent analyzes show that one in 1,000 present-day PNPLA3 variant alleles may have originated in the Neanderthal genome.”

The PNPLA3 gene is responsible for the production of an enzyme called patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 (PNPLA3). The enzyme is involved in processes that regulate the storage and release of fats. Mutations or genetic variants in the PNPLA3 gene can influence the activity of this enzyme and thus alter lipid metabolism in the liver. A certain genetic polymorphism with the reference marker rs738409 in the PNPLA3 gene is associated with an increased risk of fatty liver disease. These variations can cause the liver to store more fat and break it down less efficiently, leading to fat accumulation in the liver and increasing the risk of liver disease.