Florentine painter of the sixteenth century, Allegorical portrait of Dantelate 16th century, Oil on panel, 126.9 x 120 cm, Washington, National Gallery of Art, Samuel H. Kress Collection

From April 9th to July 16th Going through Hell: The Divine Dante will present to the public rare first printed editions of the Divine Comedy, sculptures conceived by Auguste Rodin for his monumental project The gates of hell and 15th- to 20th-century works on paper by artists such as William Blake and Robert Rauschenberg.

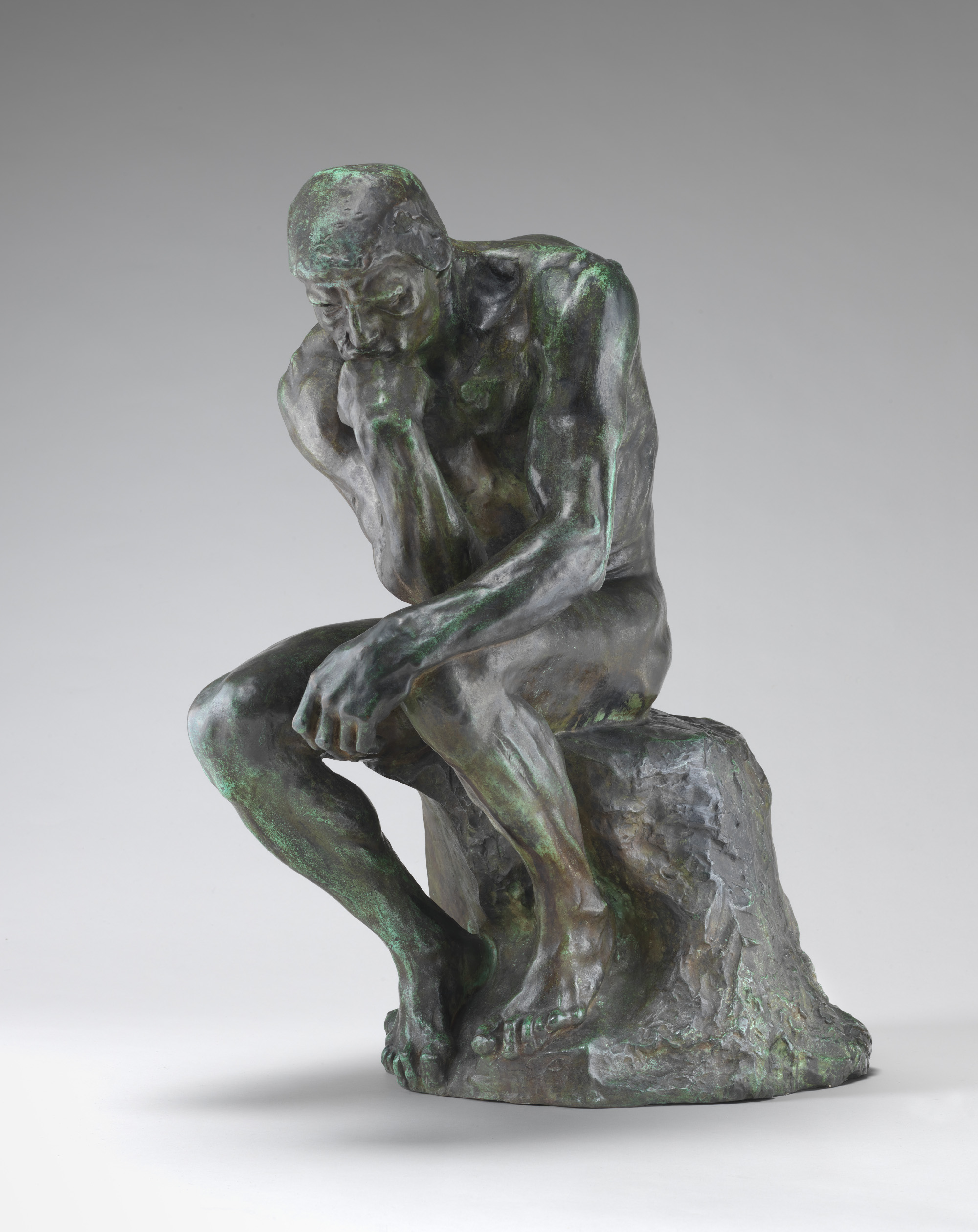

Auguste Rodin, The Thinker, model 1880, cast 1901, bronze, Washington, National Gallery of Art, Gift of Mrs. John W. Simpson

“More than 700 years after its writing, Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy remains vastly relevant to modern society – comments Kaywin Feldman, director of the National Gallery of Art -. Highlighting works from the National Gallery’s collection, this exhibition explores the enduring popularity and influence of Dante’s poem as a touchstone for artists of different ages and cultures”.

Among the most significant works of the itinerary, a Florentine allegorical portrait of Dante by a 16th-century painter stands out, portraying the poet seated on a rocky outcrop and holding a large manuscript copy of the Comedy in his hand. It opens with canto XXV of Paradise, where Dante describes his unsatisfied desire to return to his native Florence after a long exile. The drawing of the eighteenth-century Roman engraver Bartolomeo Pinelli Dante flees the wild beasts and meets Virgil (1824) instead depicts an episode at the beginning of the Divine Comedy in which the narrator meets Virgil, his guide through Hell and Purgatory.

Bartolomeo Pinelli, Dante Flees from Wild Beasts and Meets Virgil, 1824, graphite on laid paper, mounted on 19th-century album sheet, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Alexandra Bae

For centuries the Divine Comedy, particularly Hell, has urged artists to explore questions of morality and spirituality, to create metaphors for social and political issues, to reflect on the human condition. Thus the drawing by Joseph Anton Koch Dante and Virgil riding Geryon (about 1821) depicts an episode from Hell in which Alighieri and his guide descend into the eighth circle of Hell, the Malebolge. Transporting them is Geryon, a monstrous creature characterized by a chimeric body made up of a man’s face, hairy lion or bear paws, snake body, scorpion tail and demonic wings. And here it is the monster taken in Figure and Serpent by Italian-American muralist and sculptor Rico Lebrun (1900–1964) part of series Drawings for Dante’s “Inferno” (1963) populated by gruesome subjects: beheadings, immolation, cannibalism.

Made especially to celebrate the 700th anniversary of Dante’s death, 700th birthday designs Robert Rauschenberg (1965) uses the ideas received in Hell as a powerful allegory for the tumultuous social and political climate of the 1960s.

One of the most iconic sculptures of European art could not be missing from the exhibition, The Thinker by Auguste Rodin (model 1880, cast 1901), one of the first figures that the French sculptor imagined for his monumental Gate of Hell, a prospectus for an ornamental door to be placed in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. Work on the work should have been completed in 1885, but lasted for almost forty years until the artist’s death who therefore never saw his work cast, but eight multiple originals were cast from the plaster model, kept in various museums of the world.

The sculptor had decided to depict Dante’s universe of the Divine Comedy, a theme dear to him, as this work was very rich in romantic and dramatic ideas, and which Rodin knew very well. Each figure he designed represented one of the main characters in the poem. The Thinker it was supposed to depict Dante in front of the gates of Hell, meditating on his great poem.

Robert Rauschenberg, For Dante’s 700 Birthday, 1965, graphite, watercolor and gouache with silkscreen on two panels of the Strathmore Illustrative Cardboard, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of the Woodward Foundation, Washington, DC

“Dante is not only a visionary and a writer; he is also a sculptor. His expression is lapidary, in the good sense of the word. When he describes a character, he solidly represents it through gestures and poses. […] I lived a whole year with Dante, living on nothing but him and with him, drawing the eight circles of hell…” wrote Rodin.

The kiss by Rodin (model 1880–1887, cast c. 1898/1902) and The Circle of the Lustful: Paolo e Francesca (1827) by William Blake (1757–1827) both represent a tribute to the two lovers and brothers-in-law Paolo Malatesta and Francesca da Rimini, protagonists of canto V of the Inferno, who fell into temptation while reading Lancelot and Guinevere and were killed by the husband of Francesca, forever destined to wander, like damned souls similar to doves “driven by the wind”, in the infernal circle of the lustful.

Blake’s engraving portrays the couple swept up in an apparent vortex of irresistible desire, while Rodin’s sculpture surprises the lovers locked in an eternal embrace.

![]() Read also:

Read also:

• In the beginning was clay: Antonio Canova protagonist of a major exhibition in Washington