The MRI machine at Mississippi State University (MSU) in the US state of the same name uses three powerful magnets to show physicists how atoms form bonds. Chemists and biologists use magnetic resonance imaging to develop new polymers and study how bacteria bind to surfaces. A valuable investment. For all of this to work, a certain element is needed, which is constantly in short supply: helium. MSU pays $5,000 to $6,000 every twelve weeks to replenish the substance in its liquid form, which is necessary to cool the superconducting coil inside the MRI magnets to minus 269 °C.

Advertisement

“This is by far the largest expense we have here,” reveals Nicholas Fitzkee, director of the center. “The price that determines our user fees is dependent on the purchase of liquid helium – and the cost of this has pretty much doubled in the last year.” Helium is an excellent conductor of heat. At temperatures near absolute zero, where most other materials would freeze solid, helium remains liquid. This makes it a perfect coolant for anything that needs to be kept very cold.

Liquid helium is therefore essential for all technical processes that use superconducting magnets, including magnetic resonance imaging and even various fusion reactors. Helium also cools particle accelerators, quantum computers and the infrared detectors of the James Webb Space Telescope. As a gas, the substance transfers heat from silicon to prevent damage in semiconductor factories. “It’s a crucial element for our future,” says Richard Clarke, a UK-based expert in the search for helium resources and co-editor of the book “The Future of Helium as a natural resource.” And in fact, the European Union has put helium on its list of critical raw materials for 2023, and the situation is similar in Canada.

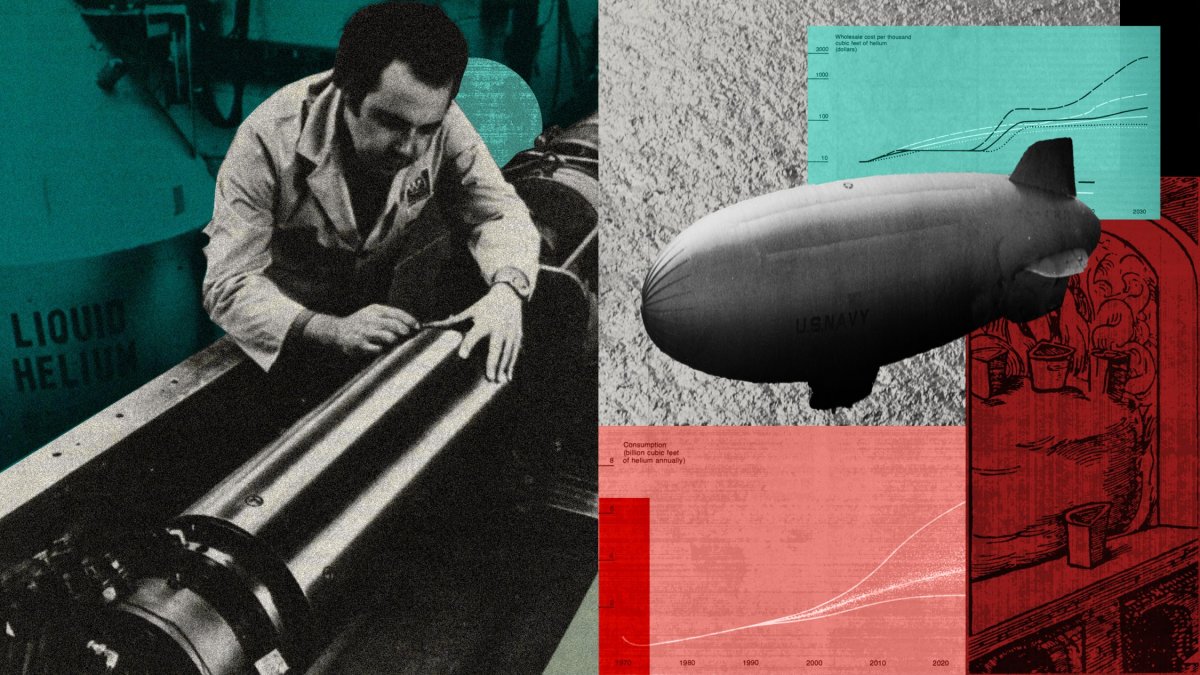

Helium has always played a crucial role in the history of technical progress, although supply is always in short supply. But how will demand change in the future? Some countries have already taken surprisingly extreme measures in the past to ensure a continuous supply of helium. An example: As early as June 1975, Westinghouse engineer H. Richard Howland wrote in the then edition of the MIT Technology Review about a controversial US program in which helium was to be stockpiled for decades. Even today the element is surprisingly rare. Global supply depends primarily on just three countries – the US, Qatar and Algeria – and fewer than 15 companies.

Hightech-Bedarf

Because there are so few sources, the helium market is particularly sensitive to disruption. If a production facility fails or a war breaks out, the element can suddenly become scarce. And as MRT Center Director Fitzkee discovered, the price of helium has risen rapidly in recent years, putting hospitals and research facilities under pressure. There have been at least four shortages in the global market since 2006, according to Phil Kornbluth, helium expert and industry consultant. At the same time, the price of helium has almost doubled since 2020, from $7.57 per cubic meter to an all-time high of $14 in 2023, according to the United States Geological Survey (USGS).

Some research laboratories, including Fitzkee’s, are installing helium recycling systems. The manufacturers of magnetic resonance tomographs are currently working on the next generation of imaging systems that require less helium. But many of the world‘s high-tech industries – including computing and aerospace – will likely require even more helium in the future than they do today. “Ultimately, helium is becoming more and more expensive,” says Ankesh Siddhantakar of the University of Waterloo, currently working on a doctorate in industrial ecology. “The era of cheap helium is probably over.”

Helium is the second element in the periodic table to have only two protons (and therefore two electrons). Thanks to their simple structure, helium atoms are among the smallest and lightest atoms, second only to hydrogen. They are extremely stable and do not react easily with other substances, making them easy to incorporate into industrial or chemical processes. An important use of liquid helium in recent years has been to cool magnets in magnetic resonance imaging scanners, which help doctors examine organs, muscles and blood vessels. But the cost of helium has risen so much and supply is so inconsistent that hospitals are looking for other options. MRI machine manufacturers such as Philips and GE HealthCare now offer scanners that require much less helium than previous generations. That could help – even if it takes years to convert the around 50,000 MRI systems that have already been installed.

Other industries are also finding ways to avoid helium. Welding shops are now using argon or even hydrogen as a substitute for some jobs, while chemists have switched to hydrogen for gas chromatography, a process for separating chemical mixtures. However, there is no good alternative to helium for most applications. What’s more, the element is much more difficult to recycle when used as a gas. In semiconductor factories, for example, helium gas dissipates heat around the silicon to prevent damage and protects it from unwanted reactions. With rising demand for computing fueled in part by the boom in artificial intelligence, the U.S. is investing heavily in building new factories, which is likely to increase demand for helium. “There’s no question that chip manufacturing will be the largest application in the next few years, if it isn’t already,” says Kornbluth.

To home page