Because of the high inflation, the ECB has been raising interest rates since July 2022, most recently by 50 basis points on March 16 despite the turbulence on the financial markets. Since their monetary policy strategy has always followed an interest rate corridor, there is a deposit rate below the base rate (main refinancing rate, now 3.5%) as a lower limit (now 3.0%) (see Fig. 1). The interest rate on the top refinancing facility is above the base rate as the upper limit (now at 3.75%). The rise in deposit rates has drawn criticism as commercial banks are now receiving large interest payments from the ECB. The interest rate hike itself has created uncertainty as the bonds held by banks are depreciating. The ECB is in a quandary!

Subsidies for miserly banks?

De Grauwe and Ji (2023) complained that banks were being subsidized by the ECB. Sonnenberg (2023) estimates the interest payments by the ECB to the banks in 2023 at 107 billion euros, of which 34 billion euros will go to German banks. If interest rates continue to rise – which cannot be ruled out – there will be even more. Losses are generated at the national central banks, so that they cannot pass on any corresponding central bank profits to the governments. As a result, the euro states are losing revenue, which is particularly painful in the current recession.

In addition, there are complaints in Germany that the commercial banks receive considerable interest payments from the ECB, but do not pass them on to households. While the deposit rate on commercial bank deposits at the ECB has risen to 3.0%, most commercial banks pay almost no interest on household deposits. According to an analysis by the comparison portal Verivox, almost half of the banks do not yet offer interest on the call money accounts (ntv 2023).

On the one hand, the interest on deposits that the ECB pays to the commercial banks can only be passed on to the depositors at the commercial banks to a limited extent, because the banks only hold around EUR 1,200 billion at the Deutsche Bundesbank, while households and companies hold around EUR 1,200 billion at the German banks. invested 3,500 billion euros.

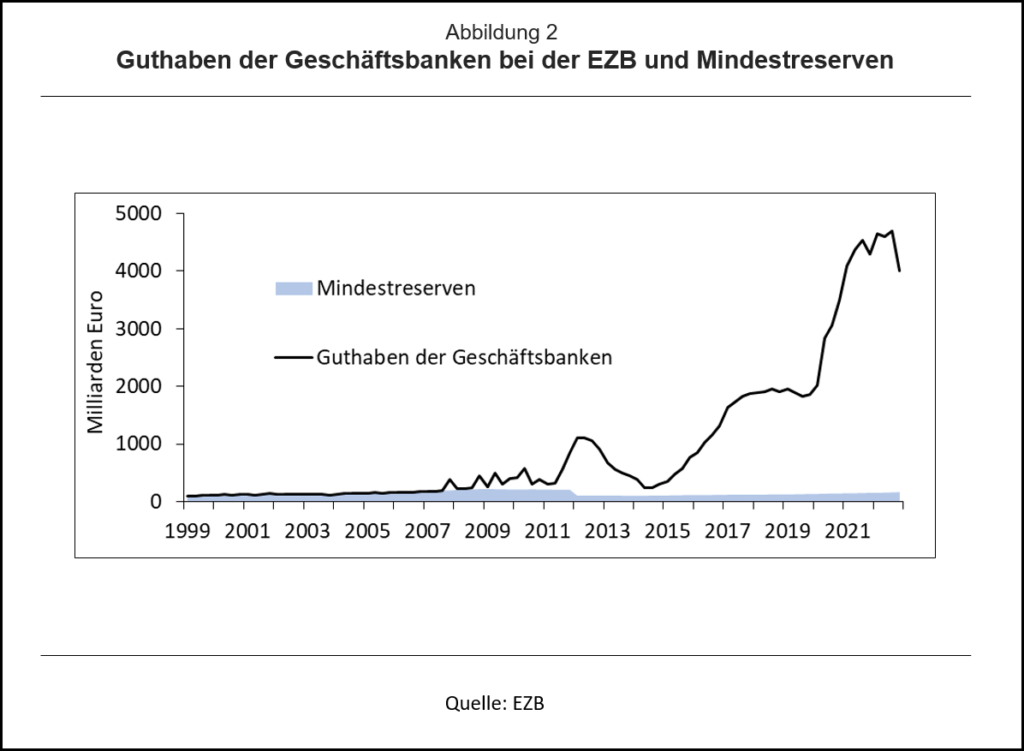

On the other hand, the criticism distracts from the fact that the problem was primarily caused by the ECB itself. Before the euro crisis, the banks only held as many deposits with the ECB as they had to due to the minimum reserve requirements. That would currently be around 166 billion euros (see Fig. 2). In this case, the corresponding interest payments by the ECB would only be 4.15 billion euros. However, in the course of the European financial and debt crisis, the ECB bought government and corporate bonds worth around 5,000 billion euros as part of the so-called quantitative easing. Since in many cases it bought these from the commercial banks, it credited the equivalent value to the banks’ accounts with the ECB.[1] Their balances have shot up far beyond the minimum reserves, to currently still 4,000 billion euros (Fig. 2).

At the same time, from June 2014 to June 2022, the ECB demanded negative interest on these balances (Fig. 1), which has long weighed heavily on the banks. The ECB’s continued low, zero and negative interest rate policy squeezed the spread between lending and deposit rates, which squeezed banks’ net interest income (interest income less interest expenditure) (Schnabl and Stratmann 2019). This is one of the reasons why the share prices of the large banks in the euro area, in contrast to American banks, remained rocky for a long time. The small and medium-sized banks had to close branches, downsize and merge.

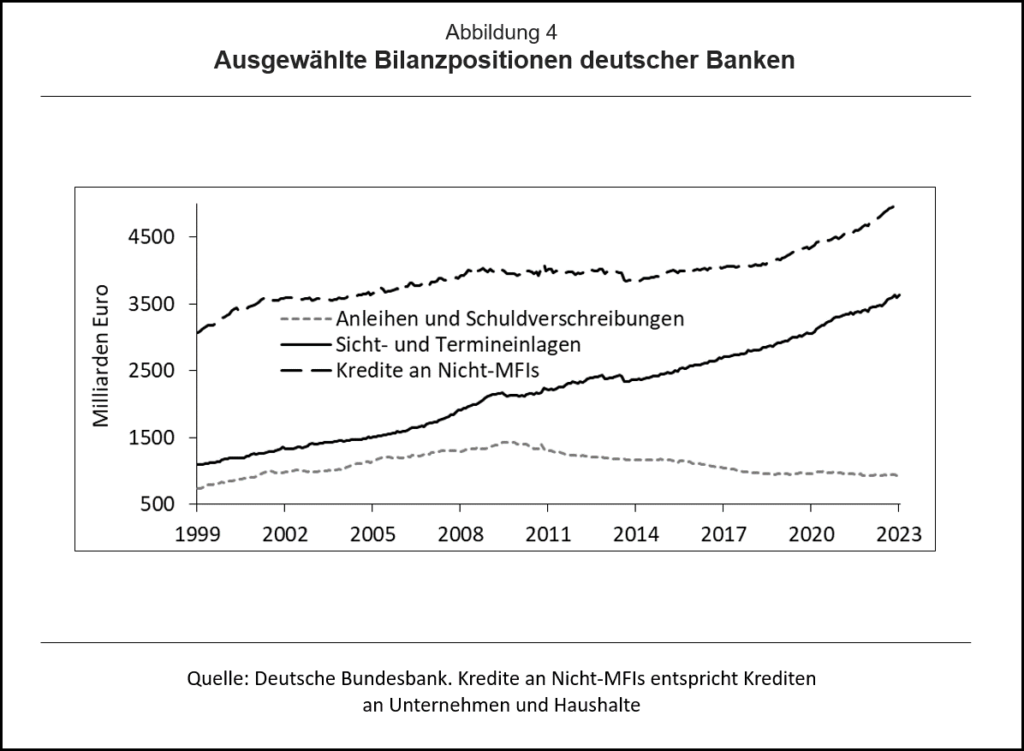

Increasing interest margins serve to prevent risks

From this perspective, the current interest rate hike by the ECB is only a normalization of monetary policy, which again enables banks to cover their costs and risks with higher credit margins (Fig. 3).[2] Customer deposits are offset by many government bonds and loans on the balance sheets of commercial banks, which, combined with the usual fixed interest rates, will continue to bear low interest rates for a very long time to come due to the ECB’s long-term low interest rate policy. The total outstanding loan volume from German banks to companies and households is currently just under EUR 5,000 billion (Fig. 4).

In particular, during the long phase of low interest rates, the banks granted many real estate loans, the default risk of which is increasing due to the current rapid rise in interest rates. Most recently, these amounted to around EUR 1,800 billion – which corresponds to around 17% of the balance sheet volume of German commercial banks. Thanks to the interest payments from the ECB, the banks can now build up reserves for possible loan defaults, since the credit margin – i.e. the difference between lending and deposit rates – has risen sharply (Fig. 3). The bankruptcy of California’s Silicon Valley Bank showed that this is important for the stability of the banking sector.

In addition, the interest rate hikes by the ECB are causing the bonds held on the balance sheet to lose value. This does not endanger financial market stability if the bonds are held until they expire and the bonds are therefore redeemed at par. However, if the banks have to sell the bonds before maturity because, for example – as is the case with the Silicon Valley Bank – many deposits are withdrawn, then the losses are realised. The affected banks can falter and pull other banks into the abyss with them.

The ECB in a dilemma

If the ECB wanted to solve the problem of interest payments to the banks in the long term, it would have to sell its government bonds to the banks, which would reduce the banks’ deposits with the ECB accordingly. Then the ECB’s interest payments to the banks would also decrease.

But the ECB is not selling bonds! Even if the bonds held expire, the ECB wants to buy more. The portfolio of bonds purchased as part of the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program (PEPP) (1,684 billion euros) will be kept constant until at least the end of 2024. The bond holdings from the asset purchase program (APP) (3,254 billion euros) will only be reduced by around 15 billion euros per month from April 2023 to the end of June 2023 by not replacing half of the maturing bonds. Overall, the ECB is reducing its bond holdings far less than the US Federal Reserve Bank and the Bank of England.

This makes the interest rate dilemma of the ECB clear. On the one hand, it wants to combat inflation by raising short-term interest rates. On the other hand, it is reluctant to allow long-term interest rates to rise by phasing out and selling the bonds it holds. The reason is probably the high level of debt in Italy, Greece and other euro countries, which raises fears of national bankruptcy if interest rates rise too much. In addition, the risk for financial market stability increases, since the banks hold many securities – especially government bonds! – hold on their balance sheets, which lose value as the ECB sells more. The volume of bonds and debentures held by German banks is currently just under EUR 1,000 billion (Fig. 4). The risk is particularly high for Italian banks, which hold many bonds from the highly indebted Italian state.

The dilemma is now being exacerbated by the fact that raising short-term interest rates is generating losses for the ECB and thus revenue shortfalls for the cash-strapped euro states. De Grauwe and Ji (2023) have proposed converting commercial banks’ currently voluntary (and interest-bearing) deposits with the ECB into non-interest-bearing minimum reserves. Short-term interest rates could then continue to rise without financial burdens on the ECB and governments. However, commercial banks would be weakened again as interest income would fall again. The banks would be destabilized, while the risk of default would increase as a result of the ECB’s rate hikes. Chancellor Scholz already felt compelled to reaffirm the security of German savings.

Bleak prospects

This means that savers’ prospects of higher interest rates on deposits are slim one way or the other, while the high inflation (most recently 8.5% in Euroland) largely created by the ECB is eating up the purchasing power of savings at a rapid pace. In addition, the destabilizing effect of the interest rate hikes by the ECB on the banks in the euro area already seems to be limiting the ECB’s scope for interest rate hikes, so that higher inflation rates can be expected in the long term.

The ECB originally started with the primary goal of price stability. Since the European financial and debt crisis, it has also assumed responsibility for financial market stability. In the meantime, neither price nor financial market stability seems to be secured. The risk is increasing that the goal of financial market stability will be sacrificed to the goal of price stability enshrined in the European treaties.

Christine Lagarde could soon make a name for herself again as the savior, this time of the banks and thus of savers’ deposits. However, the problem can only be solved in the long term if the ECB continues to cautiously raise short-term interest rates gradually and gradually sells most of its government bonds. Then the euro states would be forced to make cuts in their spending commitments. That would be painful, but would lead to a stabilization of the euro.

However, it would have been better if the ECB had never embarked on the adventures of quantitative easing and the negative interest rate policy and would have raised interest rates earlier in order to give banks, governments and companies sufficient time to adjust to the interest rate hikes.

Sources:

De Grauwe, P. und Ji, Y. (2023): Monetary Policies that Do Not Subsidise Banks. VoxEU CEPR. 09.01.2023.

ntv (2023): Nothing for call money – 282 banks still pay 0.00 percent interest. ntv 03/16/2023.

Sonnenberg, N. (2023): ECB stepping on the brake(s). Monetary Dialogue Papers, European Parliament, März 2023.

Schnabl, G. and Startmann, T. (2019): Why are our banks doing so badly? Frankfurter Allgemeine Sunday newspaper January 20, 2019, 30.

[1] The so-called targeted longer-term refinancing operations amounting to 2,200 billion euros have also increased bank deposits at the ECB.

[2] The ECB recently unilaterally canceled the negative interest rates on the targeted longer-term refinancing operations vis-à-vis the banks, so that an important source of income has been lost and the banks are repaying the loans.