In Leonardo Sciascia’s vocabulary, “land” is not only that which is cultivated, but above all the inhabited places, the women and men who populate them, the words they use, the customs and traditions, the truths and lies. And every Sicilian town “of sea or mountain, desolate plain or pleasant hill” (but especially Racalmuto) was for him, and therefore remains today for his readers, an island within the island.

Sicily, a land of singularity and separateness

Inside “that great, enigmatic container of singularity and separateness that is Sicily” (so Giovanni Raboni, reviewing Goat eye in 1984). Therefore in the incessant exploration of his land (which was also self-diagnosis, confession, love and repudiation) Sciascia moved with his calculated slowness, turning the clods with the attention of an archaeologist or a surgeon.

Loading…

Layers of cultures

Finding with an implacable gaze stratifications of cultures, duplicity of meanings, dark corners of the language that seem to say what they do not say, and meanwhile reveal something else. A memorable figure of this duplicity is the Abbot Giuseppe Vella, Sicilian by adoption, forger by vocation and Arabist for the occasion. In the pages of Sciascia he walks with fraudulent elegance on a knife blade polished by the game of languages: the native Maltese, the Latin of the liturgy, the Italian and Sicilian of political plots and daily conversation, the pseudo-Arab who he invents himself for his own Council of Egypt, winning the first chair of Arabic at the University of Palermo. Words and languages form and cover up the lie, but then they expose it.

The land on which Sciascia walked in Sicily was also a multiplicity of languages, a game of reflections between Italian and Sicilian, a cadence of marginal or inevitable words that evoke metamorphosis, transubstantiation of civilization. The “double words” give an example of this, which in a few syllables condense epochal transitions, centuries of history, encounters and clashes of peoples. Thus the word Mongibello, alternative name of Etna. A volcano with two names is already a good case, but Mongibello contains two others, Latin mons and Arabic gebel or similar, which really means ‘mountain’. Etna is therefore a mountain-mountain, champion of tautology: that is to say the same thing twice, as if one were not enough. But behind this tautology we see a centuries-old substratum: for example, the trilingual inscription of the water clock of Roger II in Palermo, where everything is said three times in an always different way, even the date: in Latin it is 1142 from Incarnation, in Greek 6650 from Creation, in Arabic 536 from Hegira. In front of this epigraph we must therefore imagine 12th-century Sicilians substantially at ease as they jump from one linguistic register to another.

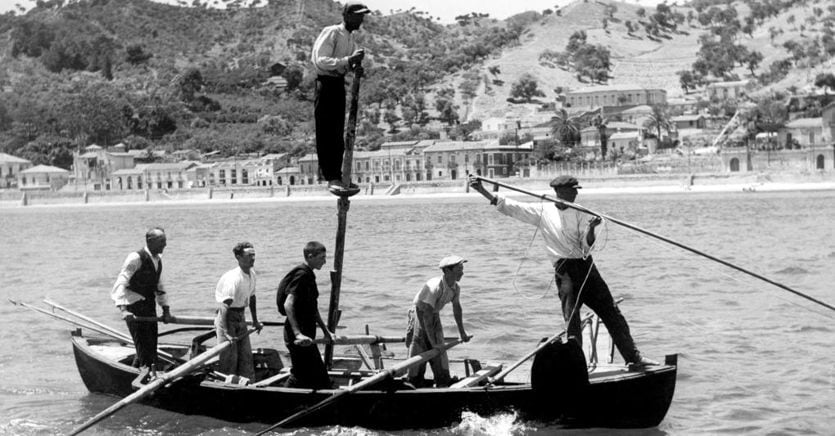

A step away from Etna, we meet the town of Linguaglossa, that is ‘language’ (in Latin or Italian) and again ‘language’ (in Greek, glossa). And then the arts, relationships, crafts. For example capurráissi, which designated the head of a boat or a trap, but also a leader or leader: and here Hulk is the Latin caput and at the same time the Italian ‘capo’, more or less exact equivalent of the Arabic rais; therefore ‘chief-chief’. Or again nannu-pappù that is, grandfather twice, first in a Latin-Romance version and then in a late form of Greek. To this range of “double” words, which dialectologists will certainly have spread out and classified, Sciascia di Goat eye he adds one of his own and playfully bases a story for you.