When he resumed power in Afghanistan in August 2021, the Taliban leadership said they would the production of opium was prohibited and duly announced the ban in April 2022. Despite Islamic law, this has been widely interpreted as part of the regime’s push for international recognition and the unfreezing of Afghanistan’s foreign assets, which remain subject to international sanctions.

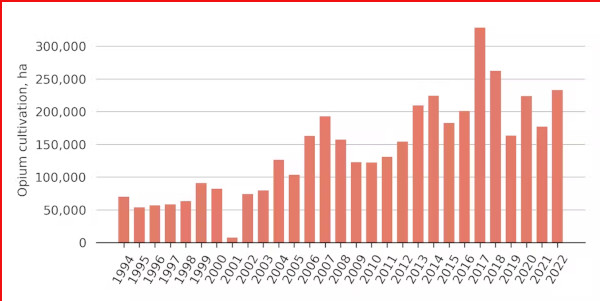

But recent data released by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) suggest that, so far, the ban has been ineffective. By 2022, the area under opium cultivation had increased by 32%, or 56,000 hectares, compared to the previous year. The 2022 harvest was the third largest acreage since UNODC began monitoring in 1994, as the graph below shows.

Previous efforts to control cultivation have had limited success in convincing farmers to stop growing poppies. The failure of the US-led eradication effort which took place from 2003 to 2009 highlighted the difficulty of physically destroying crops before harvest as a means of reducing cultivation. The total campaign cost nearly $300 million, equivalent to more than $31,000 per hectare of eradication.

This effort had little impact, in part due to the scale of cultivation throughout Afghanistan (UNODC estimates that 20% of arable land in Helmand being used to grow poppies) and the lack of viable alternatives for farmers. It was also difficult for eradication crews to operate in hostile areas.

Programs to promote alternatives to poppy cultivation have also had a limited overall effect in areas where opium cultivation is concentrated. Afghanistan’s southern provinces of Helmand and Kandahar are the source of most of the world‘s opium, and its production dominates the agricultural system.

Collected in cash

My colleagues and I are researching technological ways to monitor illicit crops. Security issues make it difficult to do it from the ground in Afghanistan, so, in 2005, we started a job that it aimed to fill gaps in generic knowledge of how to measure poppy, poppy yield and poppy eradication from satellite images. This has led to an integrated application of high, medium and coarse spatial resolution satellite data to provide critical information on cereal and poppy cultivation in Afghanistan.

Our research between 2005 and 2010 identified areas in Helmand where up to 30% of the cultivated area was used for poppy cultivation, with the remainder being mainly wheat. At the time, prices were falling, and pressure on opium production in more established areas resulted in an expansion of cultivation into former desert areas. Growers in these new areas use water drawn from deep wells for irrigation, which is a concern for future water security.

Afghan farmers are now more than ever dependent on opium for their livelihood as there are no viable alternatives to generate income. These marginal areas require investment in more expensive agricultural techniques, such as pumps to draw water for irrigation, which only opium money can provide.

Despite the lack of success in reducing opium cultivation, the Taliban was expected to succeed where others have failed. This is not just wishful thinking. Their previous ban it discontinued cultivation in 2001as the graph above shows, albeit from a lower overall opium production level than at present.

The widespread effectiveness of their ban on opium cultivation was the result of brutal enforcement in the areas under their control. Individual farmers were first warned and those who violated the ban were forced to destroy their crops along with corporal punishment and jail time.

One of the difficulties in measuring the impact of the new ban is the inevitable lag between any enforcement and the release of official figures. The Taliban’s April 2022 ban came when the growing season was already well underway, so it’s still too early to properly assess the extent to which it has been enforced. The ban announced in July 2000 halted production in the 2021 season.

Time will tell

Opium cultivation in the South actually begins every October when farmers decide what to plant. Poppy seedlings go dormant over the winter and begin growing when temperatures rise in spring. They bloom in March or April and are collected shortly after.

The UNODC’s annual survey measures poppy growing area when the crops are still green, at a time when they are distinct in the satellite images used to detect them. But the final results come much later due to the enormous effort required to produce reliable estimates. These surveys require extensive data collection, mapping of fields at sample locations, and thorough quality control before nationwide results can be released.

It’s possible that we haven’t yet seen any impact of the current policy, and that the 2023 growing season may be better evidence than the Taliban ban.

Field conditions have also changed since 2001. The analysis of the United Nations points to the growth of the illicit economy since the Taliban takeover in 2021, while the legitimate economy has shrunk, along with rising opium prices (tripling incomes in 2022), as reasons to be cautious about the effect of any new policy.

With no signs of reduced demand, much will depend on how the ban is enforced in late 2022 and early 2023. We will have to wait until the UNODC releases its next set of figures assessing the Taliban’s engagement in the ‘eradicate opium cultivation and how successful they have been in a country that remains torn by conflict.

(Daniel Simms – Lecturer in Remote Sensing , Cranfield University – su The Conversation del 07/02/2023)

the association does not receives and is against public funding (also 5 per thousand)

Its economic strength are inscriptions and contributions donated by those who deem it useful

DONATE NOW