The 1953 Giro d’Italia started on May 12 from Milan with two big favorites for the victory: Fausto Coppi and the Swiss Hugo Koblet, six years younger. Coppi had already done and won much of what made him a unique cyclist and an incomparable character for Italy in those years, so much so that he was nicknamed “the champion”. In 1952 he had won both the Giro and the Tour de France for the second time, but he was also thirty-three years old and a physique that now seemed to be as exceptional as it was fragile.

Koblet, on the other hand, was presented as someone who “knows he’s beautiful”: in Italy he was nicknamed the “blond falcon” while for French speakers he was the “charming pedaler“. But he wasn’t just blond and handsome on his bike, he was also very fast. In 1950 he had won the Giro d’Italia and in 1951 the Tour de France. For this reason it was expected that he, more than the almost forty-year-old Gino Bartali or the so-called “third man” Fiorenzo Magni, could be wheel to wheel with Coppi.

In the early days of the 1953 Giro, the Italian newspapers were mainly occupied by the Montesi case and by the electoral campaign in view of the upcoming elections, those of the so-called “fraud law”. As had already happened and as would happen again later, the sports pages dedicated to the Giro instead spent several days complaining about a race that was too wait-and-see and boring, no longer as exciting as it used to be.

Some blamed the bad weather, some on a poorly designed course and some on more tactical issues, mainly due to Coppi’s age. There was talk of a dead Giro «under the banner of “scandal also wanted”» e The print he complained of “monotonous stages without combativeness, with the large group eternally out for a walk”, asking as a remedy “a less exhausting route”, with “shorter stages” and with “the extreme difficulties not grouped in the two days preceding the last stage”.

The 1953 Giro included twenty-one stages (two of which on the same day) for a total of more than four thousand kilometres. From Milan we descended towards the Adriatic, then to Naples and from there to Rome, in a stage arriving at the Stadio Olimpico on the day of its inauguration, shortly before the national football team played there the match which they then lost 3-0 against Ferenc Puskás’ Hungary.

Coppi won the fourth stage with arrival in Roccaraso, in Abruzzo, but failed to take the pink jersey or even gain seconds on Koblet, who had accidentally hit a little girl in that stage. Neither of them was hurt too much, but the accident had led Koblet to break away from the group of his main opponents, who, in a rather unusual gesture for that cycling, agreed to slow down until they waited for them to return to the group.

The general classification was moved above all by the time trial stage with arrival in Follonica, in Tuscany, in which Koblet detached Coppi by over a minute and gained an even greater advantage over the other contenders for the pink jersey: Bartali, Magni and the Frenchman Louison Bobet. But Coppi was Coppi: Jean, Bobet’s brother and teammate who saw him whizzing by during that time trial, these who «pedaled on the air» and it was like «seeing the sun pedaling sitting on a bicycle».

Without major upheavals, the Giro continued up to Auronzo di Cadore, in the Veneto region, where the nineteenth stage started on May 31st. Koblet was still in the pink jersey and Coppi was second two minutes late. Among commentators and enthusiasts there were two prevailing positions: the first, simple, was that Koblet was stronger; the second, more theoretical, was that Coppi had only waited for that day to make a single and decisive attack. Perhaps to further fuel the myth of him, but more probably because, given his age, he preferred to concentrate the greatest effort in a single day.

The nineteenth stage was short by the standards of the time – only 164 kilometers – but before the arrival in Bolzano it included the passage next to the lake of Misurina and then on the Dolomite passes of Falzarego, Pordoi and Sella. It would be one of the most difficult stages even today, and even more so with the roads, relationships and bicycles of seventy years ago.

It was a very lively stage of attacks, defenses and counterattacks between Coppi and Koblet, with the first taking advantage uphill and the second recovering downhill. After days of waiting, tactics and “mutual guard” it was finally a direct challenge between the two strongest. The Information Courier he wrote which was “one of the most exciting battles that the history of the bicycle can remember”, a “titanic struggle” on a day in which “the glorious book of cycling has opened its epic page”. But it ended in a draw, therefore in favor of Koblet.

After breaking away, resuming and rejoining each other, Coppi and Koblet in fact arrived together in Bolzano, with Coppi winning the stage without however gaining seconds on the pink jersey. There was also talk of the possibility, as was already customary in cycling, that the two had more or less explicitly agreed for Koblet to keep the jersey and Coppi to settle instead for the victory of that prestigious stage.

Before the last stage from Bormio to Milan, without climbs and hardly decisive, however another one remained: the penultimate, from Bolzano to Bormio, with the 2,758 meters high Stelvio Pass in the middle, on which the Giro d Italy would have passed for the first time.

But it was hard to think that Coppi could turn the Giro up and down the Stelvio. Because he had just tried and failed his great attack, because the nineteenth stage had shown that Koblet could make up for the time lost on the climb on the descent and because up to that point he had simply shown himself to be better than Coppi, already described as an «old champion who has facing an ace, a man in dazzling form with the incalculable advantage of youth».

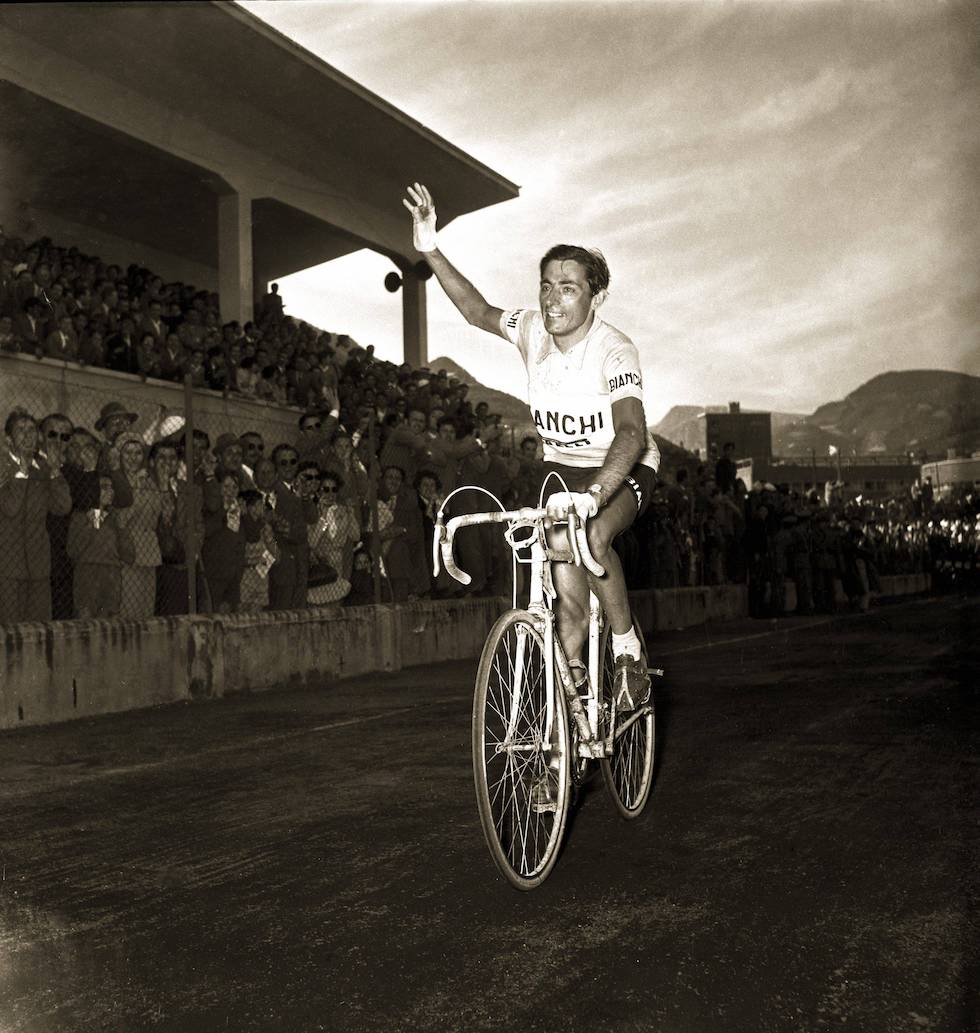

(FARABOLAPHOTO)

More than anything else, however, Coppi gave the impression of being resigned. For how and how much he complimented Koblet after Bolzano, but also because there were those who believed that the hypothetical Bolzano stage-by-shirt agreement could also be extended to a sort of general non-aggression agreement in the Stelvio stage.

It is impossible to reconstruct with certainty what happened in Bolzano between the arrival of one stage and the departure of another, but there are different versions, fed over the years by journalists and teammates; and almost never, instead, from Coppi or Koblet. One version is that Coppi was disappointed by certain bold statements by a Swiss companion of Koblet (at the time the races were divided into national teams). One maintains that Koblet celebrated too much after the arrival of Bolzano; another says that instead he had exaggerated with food or stimulating substances; still another claimed that Koblet simply had a bad night (perhaps worried by the altitude of the Stelvio, since he had suffered similar altitudes in the past) and that a teammate of Coppi’s noticed that bad night the next morning, after seeing Koblet take off your glasses for a photograph, and thus reveal your dark circles.

In short, it is not known whether Coppi had always wanted to try on the Stelvio, if he was convinced during the night for some reason, if he was convinced by someone or if – another theory – he had actually made a pact but found a way to circumvent it, that is by asking another rider who owed him a sort of favour, Nino Defilippis, to attack him on the Stelvio, in the hope that Koblet would follow him, and that Coppi could then attack in turn, given that in that case any previous agreement could have been considered dissolved.

But we only know what happened: Defilippis attacked, Koblet followed him, Coppi followed there and managed to detach them both reaching the top of the Stelvio with almost five minutes on Koblet. Despite having several problems, some of which perhaps related to one of the theories on why Coppi attacked him, Koblet recovered something in the downhill run, but not enough. Coppi arrived in Bormio three and a half minutes before him, thus taking the pink jersey.

On 2 June, with a sprint won by Magni at the Vigorelli velodrome in Milan, that Giro d’Italia ended, the fifth and last won by Coppi, thirteen years after the first, won twenty-one just before the start for Italy World War II. Only a day earlier, on the morning of June 1, there had been talk of the passing of the baton, of surrender, of his “September 8”.

It is not clear if, how and to what extent, in the hours and days after the race, Koblet took it out on Coppi: the newspapers of the time spoke of controversies, annoyances and misunderstandings, but later the two neither fed nor ever went into detail about the end of that Tour. Koblet was “a great champion and a dear friend”, said Coppi, who thanked his companions very much: “they managed to instill in me that little bit of confidence I was lacking for the final blow”.

(FARABOLAPHOTO)

In August Coppi also won the World Road Championship, the only major race he was missing and which puts him in an exclusive pantheon of winners of all the major cycling races. He said he no longer wanted to do big stage races but only one-day races – «I’ll do the Giros by car» – but he went back to doing them: in 1955 he finished second in the Giro thirteen seconds behind Magni; in 1958 he ran his last Giro and in 1960 he died of malaria.

Koblet finished another Giro in second place in 1954, the year of cycling’s first “fuga bidon”. He retired at age 34 in 1959 and died in a car accident in 1964.

The Stelvio, which before that Giro had been presented as the “mountain too many”, as too extreme a challenge for cycling, returned to the Giro twelve more times. And since 1965 the highest mountain touched each year by the Giro d’Italia has been known as Cima Coppi, and since then the Stelvio has always been the Cima Coppi of all the Giros that have passed there.

– Read also: Why Fausto Coppi?